Horrible Visions (Canto XXV)

Cantos XXV and XXVI move quickly from thought to thought such that you can almost miss what holds the episodes together, which is the transgression of right order or proper boundaries.

They both feature the poetic modesty we saw at the beginning of Inferno, but, interestingly, in canto XXV it becomes a humblebrag. Dante apologizes if his pen fails to capture how weird things are about to get, then narrates the grotesque merging of the lizard and the thief into something that is neither one nor the other, a monster we do not know how to stand before. But then before he describes the next episode, he effectively tells his poetic models, Ovid and Lucan, to sit down and shut up and watch what he is about to do:

[They] never transformed two individualFront-to-front natures so both forms as they metWere ready to exchange their substance.

Pinsky’s note to the canto nicely delineates how Dante’s Christian vision of transformation adds a moral element missing from the ancient tradition. If you’ve never read Ovid’s Metamorphoses, promise to give yourself that gift now. It is a truly wonderful, poignant, beautiful book. But the pathos of the gods turning humans into plants and animals and constellations comes from a cosmic fatalism. If the gods get involved, you’re already lost, so becoming inanimate or bestial at least spares you further suffering.

Pinsky argues that when Dante associates transformation with our own evil natures, he elevates it from the tragedy of ancient myth to something properly called Horror, “the uncanny transformation of the human body.” When the thief merges with the lizard, or when the lizard and the thief trade forms, it represents a literalization of their own (our own) moral monstrosity.

The Deep Transgression of Thievery

Most of the sins in Hell could be said to make the sinner inhuman in a moral sense, but Dante places the thieves deep in the heart of Inferno, in the eighth circle among the sins of fraud, which I looked at earlier as a class of sins against the social fabric itself. Without overthinking it, we can at least begin to see why the thieves suffer this particularly bizarre and horrifying set of punishments.

The sin of theft entails transgressing the boundary of mine and yours. This is probably less a political point about private property (as a modern Westerner might think) than a moral point about the relational nature of the exchange of goods—the concept of Jubilee, after all, suggests God cares more about a just distribution of property, and the freedom of people to own and work the land, than about strict legal claims.

But if you own something, it is in your power to sell it to me, trade it for something of mine, or even to give it to me. All these things establish and recognize a social relationship, however formal. When I rob you, I steal from both of us this just social dynamic and replace it with the law of greed and personal gain. My act makes us both less than human by injuring us in our social dimension. I am already the dust-crawling lizard I would become in Dante’s Hell.

The Desire to Know (Canto XXVI)

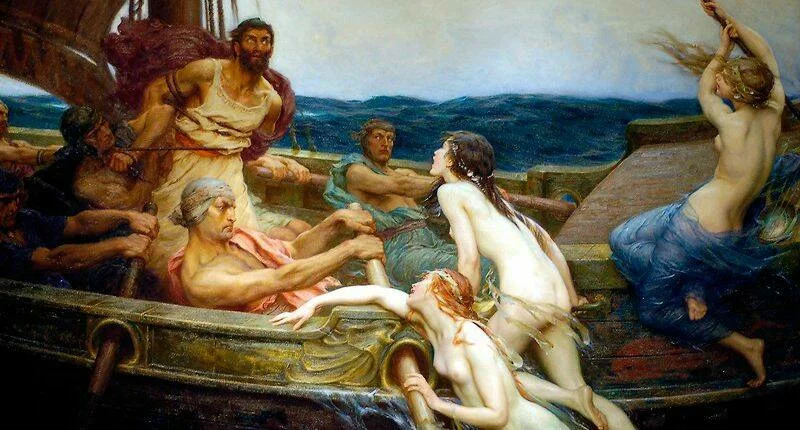

The first time I read Inferno, I was surprised to find Ulysses so deep in Hell rather than among the decent souls in Limbo. As a reasonably clever person myself, the Greek’s exploits of wit and cunning resonated with me. He pulled that wooden horse trick on the Trojans. He outwitted the Cyclops and mocked him as he escaped. He became the only man to hear the Sirens’ song and live to tell of it.

Tennyson also gives us a more ambiguous picture of the ancient hero. In “Ulysses,” he imagines the sailor after some years back home, ruling his people but feeling restless, and at last abdicating to his son so that he can lead his men to sea again. In effect, he shows us Ulysses’s journey from Homer’s epic to Dante’s comedy.

Tennyson’s ambivalence lies in two tensions: the noble virtue of courage with the political virtue of ruling and the enlightenment virtue of curiosity with the domestic virtue of the husband and father. One resonates with Ulysses’s desire to do something great, and yet one cannot shake the feeling that he should be happy with what he has at home.

That’s a modern, 19th-century view. In Dante’s view, Ulysses belongs in Hell because he gave Achilles false counsel, leading to his death. Yet Ulysses does not tell a story of deception but of abandoning his family due to his “longing for experience of the world, / Of human vices and virtue” (XXVI.94-5).

In medieval theology going back to Augustine, curiositas named the sin of excessive desire to consume knowledge and entertainments not oriented to God. Nowadays we use curiosity in a positive sense, but we still retain the sinful or excessive sense when we say something is “lurid” or holds a “morbid fascination”; we get that looking is not always innocent and therefore it is better not to look at some things.

Ulysses thus serves as an emblem of this disordered desire to know, or, put another way, of the neglect of or disdain for the boundary between what a human may rightly know and what God knows rightly. And he’s a powerful emblem just because he is so well-known in Western civilization. In Dante’s hands he becomes a figure like David or Solomon, noble but profoundly broken.

Comments

Be the first one to make a comment!