The most common motif for the relationship between science and religion is that of warfare.

It is the theme that most grasps the public mind; conflict creates good television and a fight will be considered more entertaining than friendly chatting. This motif is almost taken for granted. As many individuals can testify, it’s likely that a Christian who studies science, or a scientist who goes to theological college, will be considered an oddity, someone self-conflicted, or at the very least the subject of intensely interested questioning about how it is even possible for these two things to go together. This is true, despite the many positive contributions of notable Christian scientists, now and throughout history.

The prevalence of this assumption is not just because of the tendency of popular media to highlight conflict or laziness in public education; rather the ‘conflict thesis’—the idea that science and religion are, necessarily, opposed—is one that has been deliberately fostered and taught in Western society since the nineteenth century. The fact that so many people can think of the history of science as being a struggle for truth and enlightenment (that’s the science part) against an obscurantist church, is testimony to the success of the campaign to publicize just this theory, regardless of the facts of history. Of course science and Christianity can have a complicated relationship; but throughout history, sometimes individuals and official bodies agree, sometimes they disagree, and sometimes the two have coincided very fruitfully. So where did this overriding motif of conflict come from? How did we reach this idea that the two bodies of thought—empirical science and Christian faith—must inevitably and only ever be at war?

Certain aspects of ‘warfare’ between science and Christianity have been deliberately engineered. People with a particular personal agenda, in positions of social power, have, over the last century and more, deliberately used their influence to have their own view promulgated.

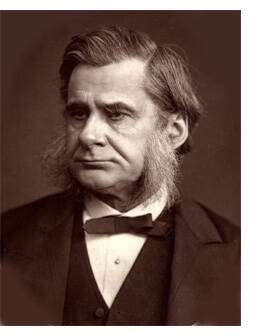

Huxley and the Professionalization of Science

Thomas Henry Huxley, for instance, was a nineteenth-century public figure who was key in creating the conflict image of science and religion. For him, it was a personal crusade to do so. Huxley was a biologist who took it upon himself to defend Darwin’s theory of natural selection. He did this so successfully and forcefully that he began to be called “Darwin’s bulldog.” Darwin himself was a quiet and retiring gentleman; he preferred to stay in the peace of his country house, and disliked controversy. Huxley, on the other hand, loved a good fight and threw himself into public debate about Darwinism, even though it’s doubtful he even believed the theory. He did, however, like the fact that Darwin’s theory was entirely naturalistic. That meant it suited a general ideological and political battle that Huxley carried on for most of his life. This was the battle to see science—not just technical science, but science as an all-embracing naturalist philosophy—take the place of Christianity as the dominant ideology in society. Huxley wanted scientists to be the intellectual leaders, and that meant they had to depose church leaders. He wanted scientists, as professional intellectuals, to have social power.

English science in the early nineteenth century was socially not much like it is now. Scientific activities were largely carried out by rich gentlemen who did not need to earn a living. It was not a career as we think of it now; it was largely privately funded, and regarded as a hobby by many. In fact, members of the nobility could join the Royal Society without ever having studied science at all; social class was more important for involvement in science than actual scientific expertise.

That meant the Royal Society was largely amateur. It did not require certain qualifications or degrees—in fact it was not easy to get what we would think of as a ‘scientific’ education—and was arranged in a fairly haphazard way. Any gentleman could take up science in his spare time and contribute to the body of knowledge, and many did, and some did so very well. This included many clergy, who might (for instance) go fossil-hunting or collect geological data.

Huxley, who like many other young men had to earn a living, was part of a rising group in the later nineteenth century that wanted science to become more professional. He and his allies sought to gain control of the scientific institutions of research and education.

Huxley wanted scientists to be the intellectual leaders, and that meant they had to depose church leaders. He wanted scientists, as professional intellectuals, to have social power.

Although it sounds like a conspiracy theory, this was exactly what happened. Through a network of informal contacts, a small group of scientifically-minded men managed to gain control of the disciplinary trajectory of science in England. One remarkable group which has come to light through historical research is the “X-club”(the name the members gave themselves). This group, which sounds like something out of science fiction, consisted of nine men, including Thomas Huxley, who would meet for dinner once a month just before the meetings of the Royal Society. Between themselves they decided whom they wished to see in power in various scientific institutions in England. They were very successful; from 1873 to 1885 every president of the Royal Society was a member of the X-club. They also managed to have friends elected to prominent positions in other scientific societies all over England

While this was happening behind the scenes, Huxley carried on the public battle. Huxley wanted men of science to be seen as intellectual leaders. He wished to see science itself have intellectual independence; in particular, to be free from religious opinion. It was a battle for who had the right to say what was true. Huxley wanted this right to belong to scientists, not theologians. He did not try to abolish religion altogether, but he wanted it to be reduced to a matter of feeling, not intellect, and he wanted it to lose control of education and public opinion. In the arena of knowledge and

THOMAS H. HUXLEY

thought—matters of truth and reality—science had to emerge as the leader. There was only one kind of knowledge, he insisted, and the only way of acquiring it was by means of scientific analysis. His commitment to scientific naturalism was, in fact, almost a new religion. He would speak of the “church scientific,” with himself as a bishop, and his lectures as ‘lay sermons.’

Huxley championed science against theology, and insisted on the superiority of science. He and his friends publicized and popularized the successes of scientific method; the improvements in industry, for instance. What Huxley was proclaiming, however, was not merely science as an activity, but science as a naturalistic philosophy; that is, the philosophy that there is no God, or not one worth paying any attention to. The success of science as an activity was used to defend science as a philosophy. Huxley did not merely want scientific technique and knowledge taught, but he wished naturalism to become the dominant ideology in society—and for theology to lose its place amongst the intellectual leadership.

Huxley’s main technique for doing this was to state constantly that science and theology were opposed to each other, and that in this battle, science won. Huxley presented science as a great force of progress marching forward, constantly opposed by Christianity but inevitably triumphant. Huxley was a very powerful public speaker, as well as being a popular writer. Moreover, he spent most of his professional life engaged in public debates. In time, people began to believe him.

Draper, White, and the Conflict Narrative

When two works were published later in the nineteenth century, dealing with the relationship between science and religion, Christianity became more firmly established as the ‘enemy’ of science. Both books gave voice to the bitterness that each man felt for established religion, arising from their life experiences.

Draper’s History of the Conflict

John William Draper (1811-1882) was a professor of chemistry in New York when he was asked to write a popular history of science and religion. The title of his work, “History of the Conflict Between Religion and Science,” reveals precisely what he thought the relationship between science and religion was. “The history of Science is not a mere record of isolated discoveries,” he wrote, “it is a narrative of the conflict of two contending powers, the expansive force of the human intellect on one side, and the compression arising from traditionary faith and human interests on the other.”John William Draper, History of the Conflict between Religion and Science (London: Kegan Paul, Trench and Co, 1883) p. vi. Draper’s book was a vehement attack on the Catholic Church; as a work of history it was, by most standards, poorly written. However this did not prevent it from becoming a massive success.

White’s History

Similar literature followed, but Andrew Dickson White’s work is worthy of special mention. Originally from an Episcopalian family, White was elected to the State Senate of New York in 1863. After the election, he persuaded the philanthropist Ezra Cornell, a fellow-senator, to support the founding of the (non-sectarian) Cornell University. The bill was vehemently opposed by local denominational colleges and the secular press were drawn in.

White was angered by the attacks made on his university and, as a result, gave a lecture in New York that presented historical examples of conflict between science and religion in order to show that science always emerged victorious. The lecture was printed in full and widely disseminated. White eventually expanded it into a popular book, The Warfare of Science. Finally, in 1896 he published a two volume work, A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom. The theme is by now familiar:

In all modern history, interference with science in the supposed interest of religion, no matter how conscientious such interference may have been, has resulted in the direst evils both to religion and to science, and invariable; and on the other hand, all untrammeled scientific investigation, no matter how dangerous to religion some of its states may have seemed for the time to be, has invariably resulted in the highest good of both of religion and of science.Andrew Dickson White, A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom (New York: Dover, 1960) p. viii.

The historian White had written a far better book than Draper’s. Moreover, White was not trying to create a war; he insisted that he greatly admired many clergy. He did not claim that science and religion were inherently enemies. Rather, he argued that people had only too often attempted to defend religion in a way that was actually detrimental to the pursuit of truth and what was best for society. He was not so much attacking religion as expressing extreme exasperation against those people who would obstruct, in the name of religion, what he saw to be work for the good of mankind.

However noble his intentions, this was not what the public heard. White’s book was taken to have declared science and religion irreconcilable enemies. Draper’s book added a note of bitterness. The notion that, historically, science and theology had always been in conflict, became accepted as fact. It began to be a commonplace theme in textbooks and academic literature. Research has shown how inadequate this characterization of the relationship is; nonetheless, the idea has gripped the public mind, and continues to have enthusiastic proponents.

Huxley’s aim to see science and Christianity established as enemies has largely succeeded. It is by far the most common metaphor for discussion of science and Christianity. It is a powerful metaphor, but a ridiculously improper one for anyone interested in understanding our world. Let us hope that in a new century we can do better.Based in part on excerpts from Kirsten Birkett, Unnatural Enemies: an Introduction to Science and Christianity (Sydney: Matthias Media, 1997).

Comments

Be the first one to make a comment!