On December 25th, we commemorate the story of the King and the beginning of his mission.

To hear it fresh we will tell it a bit strangely. And so this story of a king is also the story of a kingdom. Many hundreds of years before, this kingdom had been divided into two, north and south. Over time, the northern kingdom fell to invaders while the southern kingdom survived, continuing the unbroken line of their forebear, which was foretold never to fail. But fail it did, or so it seemed, and the royal house suffered exile, disgrace, and worse—it was forgotten. The restoration of the true king became something expected only by a remnant, those with long memories and steadfast faith. When the time was ripe, and the child who would be King was born, his parents fled with him from their homeland and lived in another exile, fearing the evil powers seeking his life. They called him Hope.

When he grew to maturity, he spent his time wandering from place to place, without honor in his own country. He gathered a small group of friends and followers, those who knew his name. He knew he would be king, but he kept himself hidden, not letting those who knew his true nature move him to the throne before the appointed season. Those who held the throne in the pride of earthly power would never accept him. When the time was ripe, however, he came to his royal city—not in triumph, but as a bringer of healing. He had been there many times before, of course, but this time was different. This time the people who had once ignored him whispered like fire in the streets: the King has come back! But he did not take his throne, even then. Instead, as it had been foretold that he trod the paths of the dead and led death captive, suffering outside the walls of the city, he marched then into the gates of hell where the Evil One was cast down.

That was his victory, and the victory which led to the restoration not only of his crown but of all things. His kingdom, so long travailing under the oppression of the dark enemy, was free. The King reigned in justice. He became the king of the new united kingdom, and of much more. The people of his kingdom had lived so diminished for so long that they had forgotten what a true Man was meant to be. But here, in this king—the rightful son of the first man, the rightful heir to the blessed kingdom—the beauty of God’s purpose for Man shone forth undimmed. And after this mighty warrior triumphed over evil, he became a bridegroom, finally fulfilling the pledge he had made so many years ago. He restored and renewed all things, and set to rights all that had been bad and broken in the world, even to the ends of the earth. But all of this began on December 25th.

The 25th is, of course, the day that the Fellowship of the Ring departs from Rivendell on their quest, and the king is Aragorn.

Aragorn is portrayed as a Christ figure—that’s obvious. But it’s less obvious just what sort of Christ figure Aragorn is. He doesn’t die and return like Gandalf; he doesn’t endure the sacrificial and mediatorial suffering of Frodo. Aragorn is the coming and reigning King.

He’s also the main human hero of the story, and for Tolkien, to be a Man is about much more than being the “normal” species in a world populated by Elves and Dwarves. In fact, to be a Man and to be a King are intimately related.

Tolkien’s Hierarchical Universe

Tolkien constructed an explicitly hierarchical universe. Among mortal beings, God placed Men and Elves (his “children”) above Dwarves and other intelligent creatures, and these above animals. Men, the late-comers, themselves hold a special destiny that sets them apart from Elves—they are free from the weave of fate, their destiny after death is a mystery to the Elves, and it is even rumored that Eru Himself will one day walk as one of them. While Elves are bound to the circles of the world, Men will transcend them. They are the centerpiece of creation.

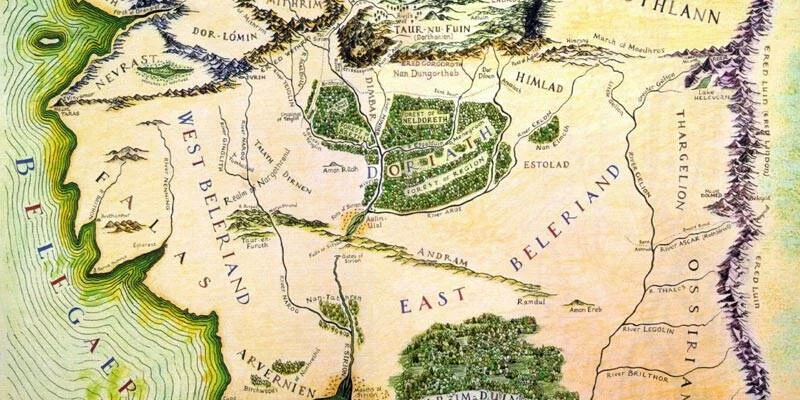

But among Men, the kingdom of Númenor acts as the people specially blessed of God, and when Númenor is destroyed for its rebellion, a single faithful branch of the royal family is preserved. This is Elendil, with his two sons Isildur and Anarion, who will rule the kingdoms of Arnor and Gondor and eventually defeat Sauron for the first time in the Last Alliance. The bloodline of Númenor is almost sacred, coming as it does down from generations upon generations dwelling within sight of the shores of Valinor. The heirloom of the kings is the Ring of Barahir, given by Finrod the Elven-King himself, who first discovered Men in the world. So Aragorn eventually wears on his hand a signet that betokens an Adamic heritage, a special preeminence.

Tolkien often hints at the dangers of intermixing with other, lesser lines, and by the time of The Lord of the Rings the people and princes of Gondor have fallen far from the pure (because divinely blessed) Númenorean lineage. Middle-earth is unabashedly monarchist and probably Pseudo-Dionysian too (remember the Valar and Maiar?). We may balk at such thinking. But before we do, we should ask how this sort of hierarchy and supremacy play into (1) Aragorn’s typifying of Christ, and (2) Aragorn’s epitomizing of humility, service, and sacrifice.

Tolkien is appealing to the beauty of an ordered creation—a particularly pre-Modern, medieval beauty. Planets revolve in circular orbits, animals typify human virtues. The whole human edifice is constructed like a multi-tiered wedding cake. And the King is the topper. For most of human history, the king was the guarantor of order in society and the safeguard against chaos. He was the link between the people and the land, between the ploughman and the Most High God. He existed for the sake of the people, and received special privileges in recognition of this. The Bible has a hierarchy too—not of ontological status, but of holy instruments. God continually refines and narrows His chosen vessels until God’s agent in the world culminates in a single, supremely significant individual.

Matter → Animals → Humans → Abraham → Israel → Judah → David → Jesus

In Middle-earth, the hierarchy familiar to Jews and Christians is amplified.

Matter → Animals → Thinking beings → Elves → Men → Númenor → Elf-friends → Line of Elendil (the kings) → Aragorn

The King of the united realms of Arnor and Gondor is not merely some puissant political figure. This is the King descended from Eärendil the Blessed, from Beren and Lúthien, from Melian the Maia, from Elros brother of Elrond. Aragorn is the descendant of two houses of Elves who dwelled in the heaven of Valinor, an angel, all three noble houses of the first Men. . . In short, virtually every noble hero and royal house of the Silmarillion flows down into Aragorn. He is a cosmic King, reunifying the disparate and broken elements of Middle-earth, tying the frayed strands of the story into a single cord. In him the races of Elves and Men, mixed only thrice before (and all among his ancestors) intertwine, gifting the world with the bravery of Men and the beauty of Elves, turning the West into a triumphant and glorious kingdom of light—a restored creation. All that is sad comes untrue under Aragorn’s just hand, as he returns ancestral lands in good faith and exalts the humble.

The Hands of a King

That is the point, after all—the ruler with an iron fist and a single indomitable will is not Aragorn but Sauron. Aragorn comes into his kingdom not as a conqueror but as a servant, humble and other-centered. As they said in Gondor, “The hands of the king are the hands of a healer, and so shall the rightful king be known.” So it is in fact through Aragorn’s service toward others that his kingship is revealed, and his people’s loyalty is secured by his refusal to seize the crown before political peace can be assured—demonstrating that he places their welfare above his own power. If all of creation invests its authority and glory in the single figure of King Elessar Telcontar, he immediately returns the gifts entrusted to him with grace and kindness. When Frodo and Sam come to Aragorn’s celebration feast at the field of Cormallen, Aragorn rises from his throne and places upon it these two hobbits, still dressed in their orc-rags. The king deigns to create a mutual interweaving of honor and ebullient, joyful giving between himself and his subjects. He gives back tenfold what is offered to him, and so he himself increases in honor.

But of course, that is the end of the story. On December 25th, Aragorn looks like nothing so much as a weathered, scraggled, hard-bitten wild man. Boromir refuses to accept his claim to the throne. The hobbits have in all likelihood never even heard of Gondor. Here, on this side of Mount Doom, Sauron seems invincible and the very thought that he could be overthrown, that the King should have his crown again, seems awkward and escapist.

But the Wise know. Gandalf, Elrond, Galadriel—even Bilbo Baggins of Bag End—they believe.

All that is gold does not glitter,

Not all those who wander are lost;

The old that is strong does not wither,

Deep roots are not reached by the frost.

From the ashes a fire shall be woken,

A light from the shadows shall spring;

Renewed shall be blade that was broken,

The crownless again shall be king.

Tolkien firmly believed in the power of fiction, what he called sub-creation, to illuminate truth and give “glimpses” of the reality we often ignore. And it seems rather common that we often ignore the cosmic epic of Christmas. Another Christian writer, G.K. Chesterton, put it this way in “The Ethics of Elfland”:

“These tales say that apples were golden only to refresh the forgotten moment when we found that they were green. They make rivers run with wine only to make us remember, for one wild moment, that they run with water. . . All that we call spirit and art and ecstasy only means that for one awful instant we remember that we forget.”

The power of good fiction is precisely that it reminds us of the wonder of the real. This Advent, let us remember the King who came through many dangers into His kingdom, and now places the crown upon the heads of His people. In the Incarnation, let us proclaim that the blade that was broken is reforged, and is wielded to cut a mortal blow against death and sin. In this Man, the true Man, the jewel in the crown of all creation, we see that for which all things have been waiting in eager expectation, that which we all along ought to have been, the recapitulation and restoration of all that has come before. Everything sad comes untrue. But it starts on December 25th.

Comments

Be the first one to make a comment!