Previously, I argued that achievement is relative. Various factors shape how we evaluate it. What is a great achievement for some is no big deal for others. One person’s “normal” might be an outstanding achievement for someone else.

Today, I want to suggest that a key factor that underlies the relativity of achievement is potential. Whether we are conscious of it or not, we tend to evaluate achievement in light of an individual’s potential to do well.[1]

What do I mean by “potential”?

I don’t just mean a person’s inherent giftedness or natural abilities, though that’s a big part of it. I think we need to include all possible factors that might go into a “Small, skinny, young David slew the giant, unbeatable warrior named Goliath. Wow. What an achievement!”person’s potential to achieve. That includes natural ability, but it also includes education, socioeconomic background, opportunity, and personal issues or struggles.

A person who comes from a wealthy, privileged, highly educated background, who is also endowed with natural gifts, has huge potential for achievement in this world. We intuitively know this, and therefore expect great things from such a one.

Another person who lacks that kind of head start has less potential for achievement. Now, that doesn’t mean such a person will not achieve—often they do very well, against the odds. But that’s my point, we recognize that their achievements are “against the odds,” because we know that the odds favor potential. This may not seem fair, and I’m not claiming it is. But it’s the world we live in, right?

An orphan born in India who grows up on the streets, has no education, and is oppressed by the wealthy, has far less potential to achieve than the average kid growing up in America. And so it is all the more remarkable when an Indian orphan overcomes all obstacles to achieve great things. When she ends up going to medical school, builds a medical center in a rural village, and provides free health care to the poor, such as young orphans like her, we all know it is an incredible achievement.

If an American did the same thing, and built a medical center in a rural village in India, it too would be a wonderful achievement. But for the disadvantaged Indian orphan to do that, it would be seen as a remarkable achievement, because her initial potential was so much smaller than the average American.

Having said all that, “potential” gets more complicated when we think about the way that adversity can affect us in positive ways. The chief point that Malcolm Gladwell argues in his book, David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits, and the Art of Battling Giants, is that facing fierce adversity is one of the factors that produces some of the greatest achievers in the world.

Having said all that, “potential” gets more complicated when we think about the way that adversity can affect us in positive ways. The chief point that Malcolm Gladwell argues in his book, David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits, and the Art of Battling Giants, is that facing fierce adversity is one of the factors that produces some of the greatest achievers in the world.

If we include this observation in the concept of “potential” we may end up saying that disadvantage actually gives people an edge over those who have a comparatively easy life.

But the reality is that most underprivileged people do not do as well as the privileged. Gladwell’s thesis helps to explain some super high achievers’ grit and determination, but it can’t be used to say that all disadvantaged people actually have more potential for achievement than the privileged. Just look at the world around us. It’s not what we see.

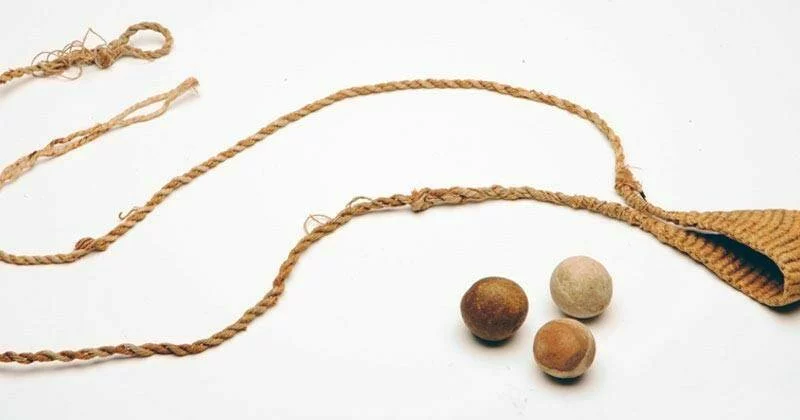

But Gladwell helps me to make my bigger point. It is all the more impressive when the Davids conquer the Goliaths of this world. The reason is that we measure achievement by potential. Small, skinny, young David slew the giant, unbeatable warrior named Goliath. Wow. What an achievement!

Speaking of David and Goliath, next week we’ll begin to look at the Bible and how it ought to shape our thinking about achievement.

[1] I want to clarify that in these “defining achievement” posts, I’m just trying to articulate what we, as a culture and society, think of achievement. I’m not arguing that this description is morally right or wrong, godly or ungodly. We’re not at the stage of evaluating things yet, but that will come later.

Comments

Be the first one to make a comment!