“What makes a people great?” I contemplated this question during the Black Church Studies conference last month, along with a few other questions that I’ve reflected upon in previous posts (“The Church as Channel of Jubilee,” “What is the black church?“, and “What is Justice?“). But only until recently could I pinpoint a potentially foundational reason why this question matters.

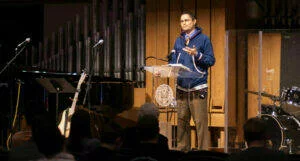

It was in the context of a profound message presented at the recent “Justice Conference” (June 5-6, 2015, in Chicago) by Pastor Eugene Cho that named a fundamental goal I wanted to achieve in a contemplation of this question. Pastor Cho spoke of the danger of making other people “projects,” even in the effort to actualize justice. He further argued that a “project” is dehumanized by nature and thus there is a loss of “reciprocity” in the relationship. He did not delineate Reciprocity requires mutual contribution. A “project” is not regarded as being able to contribute to the enhancement and development of the other.the meaning of all these terms and concepts specifically, but I wanted to springboard off this thought to flesh out my concern.

“Projects” are those who need to be taken care of, spoken for, protected from seemingly insurmountable foes, subject to diminished expectations in multiple areas and subject to sympathy. These are dehumanized because they are not regarded and treated as having agency, a capacity for responsible pursuit of their goals. Reciprocity requires mutual contribution. A “project” is not regarded as being able to contribute to the enhancement and development of the other. Pastor Cho’s language and conceptual framework crystallized the way that some, even well-meaning members of the dominant culture, regard many African Americans.

My overarching intent is to develop a vision that exhorts more African Americans toward agency and the belief that they have much to contribute to their communities and to the dominant culture in every area. To prevent others from regarding them as a “project,” I suggest a pathway of actively achieving greatness. There is a greatness that focuses much on external achievements whether in areas like athletics, the arts, the financial world, and the sciences. But even these achievements often begin with the development of internal character individually, and also that which arises in some type of character building community.

Augustine: Looking back and looking forward

I believe that it must begin with the teaching and modeling possible in the church. I frame it, however, in terms of the pursuit of virtue. In so doing, I will be consulting with Augustine who, at times, was a perceptive student of human civilization and knowledgeable of what makes a person, or a people great. One of Augustine’s reflections on virtue takes place in the City of God, XIX, 4.

The four cardinal elements begin with temperance, “which reins in the desires of the flesh to keep them from gaining the consent of the mind and drawing it into every sort of degrading act” (New City Press, vol II, p. 355). Augustine understands prudence as that which “teaches us that it is evil to consent to the desire to sin and good not to consent to the desire to sin” (p. 356). He writes of justice, “whose function is to assign to each his due—as a result of which a certain order is established in man himself, so that the soul is set under God, and the flesh is set under the soul, and thus both the soul and the flesh are set under God” (p. 356). Fortitude “bears the most evident witness to human evils, for it is precisely these evils that it is compelled to endure with patience” (p. 356).

I will have more to say on these themes in future reflections. Suffice it here to say that those who pursue these things will not be regarded as a “project,” and as such they will be respected with their dignity upheld.

Comments

Be the first one to make a comment!