What would it be like to learn you would carry the infinite God within your womb?

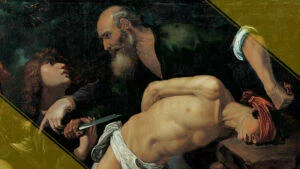

This ekphrastic poem (fr. Gk ekphrasis, a rhetorical exercise of describing a work of art) follows Botticelli’s lead in opening up a space of consciousness between Gabriel’s message and Mary’s bold acceptance. The poem is both meditation and art criticism. It interprets the painting, which is itself already an interpretation, and both invite interpretation from the reader. Thus, this poem about a painting about the annunciation of the incarnation participates in our own embodiment through imaginative conversation with other minds.

The Costello Annunciation

Botticelli’s Cestello Annunciation

The angel has already said, Be not afraid.

He’s said, The power of the Most High

will darken you. Her eyes are downcast and half closed.

And there’s a long pause—a pause here of forever—

as the angel crowds her. She backs away,

her left side pressed against the picture frame.

He kneels. He’s come in all unearthly innocence

to tell her of glory—not knowing, not remembering

how terrible it is. And Botticelli

gives her eternity to turn, look out the doorway, where

on a far hill floats a castle, and halfway across

the river toward it juts a bridge, not completed—

and neither is the touch, angel to virgin,

both her hands held up, both elegant, one raised

as if to say stop, while the other hand, the right one,

reaches toward his; and, as it does, it parts her blue robe

and reveals the concealed red of her inner garment

to the red tiles of the floor and the red folds

of the angel’s robe. But her whole body pulls away.

Only her head, already haloed, bows,

acquiescing. And though she will, she’s not yet said,

Behold, I am the handmaid of the lord,

as Botticelli, in his great pity,

lets her refuse, accept, refuse, and think again.

Andrew Hudgins, in Upholding Mystery: An Anthology of Contemporary Christian Poetry. Ed. David Impasto. Oxford University Press, 1997.

Comments

Be the first one to make a comment!