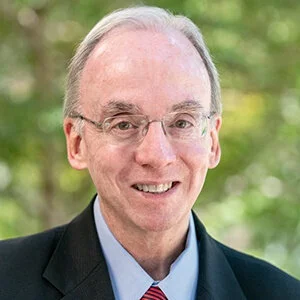

Peter Berger, one of the premier sociologists and public intellectuals over the past fifty years, passed from this life on June 27th at the age of 88. For years I had hoped for the privilege to meet him, but that opportunity never developed. Thus, I offer this tribute not as a friend or even an acquaintance, but as an avid reader, admirer, and student of his numerous publications.

In 2011, Berger’s publication Adventures of an Accidental Sociologist: How to Explain the World Without Becoming a Bore, which served in many ways as a memoir of his career, explained how he stumbled into the world of sociology while providing readers a window into the key intellectual issues that motivated his career.

Prior to his retirement, Berger had taught at Boston University since 1981 where he founded the Institute of Culture, Religion, and World Affairs and also served as the director of the Institute for the Study of Economic Culture. He had spent a number of years on the faculty at The New School for Social Research, Boston College, and Rutgers University. A native of Austria, Berger immigrated to the United States following World War II.

Berger’s 1966 publication, The Social Construction of Reality, written with Thomas Luckmann, was the influential work that propelled Berger’s career forward to eventually become arguably the best-known sociologist of our day. It was his intense interest in religion that made his work so valuable to theologians, pastors, and Christian leaders. Berger did not identify as an evangelical, but as—in his words—an incurable Lutheran. The Sacred Canopy (1967) offered a window into how religion enabled people to make sense of life and the world by providing a sheltering tent under which all of life could make sense.

Several of Berger’s most influential books were published during the social revolution of the 1960s and ‘70s. This revolution took place on multiple fronts, aimed at several targets, but one of its primary focuses was religion itself. During this time, some elite thinkers suggested that “God is dead.” People began to see the breakdown of denominational identity, including observable divisions between progressives and evangelicals. The coherent world that seemingly existed in North America in the 1950s, according to Berger, no longer existed after the social revolution. Instead, the world had become more disconnected with the growing influence of secularization, especially across Western Europe and among the intellectual elites in North America, It was his intense interest in religion that made his work so valuable to theologians, pastors, and Christian leaders.the expansion of pluralization, the aloneness of privatization, resulting in what Berger described as cognitive contamination along with the loss and breakdown of plausibility structures.

Berger pushed back against trends among progressive theologians, who rejected traditional orthodoxy, doing so particularly in his book A Rumor of Angels: Modern Society and the Rediscovery of the Supernatural (1969). Earlier in his career, Berger advocated a theory of secularization, which suggested that as the world has become more modern it increasingly becomes more secular and less religious. Due to the rise of Christianity in the Global South, the expansion of Pentecostalism in North America, the growth of evangelical scholarship in the American Academy, and the increased influence of Islam in many parts of the world over the past several decades, Berger proposed that secularization was truly only a reality in Western Europe and among many intellectuals in North America. Expanding on these themes, Berger co-authored Religious America, Secular Europe? (2008). The American experience of growing modernization combined with intense religiosity, especially across the heartland, led Berger brilliantly to describe the United States as “a nation of Indians (based on the observation that India is the most intensely religious nation on earth) ruled by an elite group of Swedes (based on the notion that Sweden is the world’s most secular nation).”

In The Heretical Imperative (1980), which was not a book about theological heresies, Berger argued that each individual must choose his or her own religious identity. In 2010, Berger expanded these thoughts with In Praise of Doubt: How to Have Convictions Without Becoming a Fanatic. He proposed that religious and moral beliefs, along with worldviews in general, can no longer be taken for granted. In a multi-authored work, edited in 2010, Berger continued this conversation under the title Between Relativism and Fundamentalism: Religious Resources for a Middle Position. If I have rightly understood Berger in these two works, I would have some lingering questions regarding the conclusions that Berger has offered. Instead, I think a better option for us from this eminent sociologist is found in his words at Gordon College just a few years ago.

In 2013, Berger offered these wise words in a visit to the Center for Faith and Inquiry at Gordon College, which serve as an important and timely reminder for the evangelical community in general, saying:

I think that Evangelicals so far have resisted what has been I think the main sin—I wouldn’t call it a sin—the main mistake of Mainline Protestantism, which is to replace the core of the gospel, which has to do with the cosmic redefinition of reality, with either politics or psychology or a kind of vague morality, which is not what I think the Christian gospel is basically about. The Christian gospel is about a tectonic shift in the structure of the universe, focused on the events around the life of Jesus. Obviously there are a lot of implications to this. Evangelicals have not gone through this process. Luckmann many years ago called it “inner secularization.” Either it becomes politicized: what is Christianity all about? It’s some political program, which tends to be left of center, now it could be just as well right of center. That’s a distortion. Or it becomes psychologized: it has to do with well-being and self-realization, Norman Vincent Peale type stuff. Or a kind of vague morality, which is usually something that most people would certainly approve of: don’t be nasty to little old ladies if they slip in the gutter. Okay, fine. But again, that’s not what the gospel is about. And that is something Evangelicals have retained, and I think, and I hope, will continue to retain.

Professor Berger’s influence has been far-reaching and incredibly significant. His prolific publications have influenced people in many spheres, religion, psychology, anthropology, political science, as well as sociology, for more than six decades. He collaborated on several books with his wife, Brigitte Berger, herself a prominent sociologist and author. They were married in 1959; she died in 2015. He is survived by his two sons, Thomas and Michael, and two grandchildren. It is a joyful privilege on this day to join with countless others, who have been helped, guided, and shaped by Peter Berger’s life, writing, and thought, to offer thanks to God for his life, influence, and legacy.

Comments

Be the first one to make a comment!