The natural sciences may be the most powerful achievement of the human mind. The eradication of polio, the feats of biotechnology, astronomy’s insights into the gaping universe, all of these modern wonders and a host of others are the fruit of scientific research.

We are all beneficiaries of this remarkable gift, we rely on medicine, we drive cars, we consult daily weather reports. Like it or not—after all, science is a mixed bag—it is the world in which we live, move, and have our being. Perhaps we should not be surprised that “science” itself is aLike it or not—after all, science is a mixed bag—it is the world in which we live, move, and have our being. contested concept, a set of practices so central to the habits and self-conception of the modern world that it inevitably invites conflicting interpretations.

A focal point of debate involves the intellectual legacy of Charles Darwin. His theory of evolution made it possible to think that God was unnecessary to the origin and development of life—undirected natural causes can explain everything. As Richard Dawkins once remarked, “Darwin made it possible to be an intellectually fulfilled atheist.”Richard Dawkins, The Blind Watchmaker (New York: Norton, 1996), 7. Of course, premodern thinkers would have been shocked. “Throughout the Christian era,” points out William Dembski, “theologians have argued that nature exhibits features which nature itself cannot explain but which instead require an intelligence beyond nature.”William Dembski, The Design Revolution: Answering the Toughest Questions about Intelligent Design (Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 2004), 66.

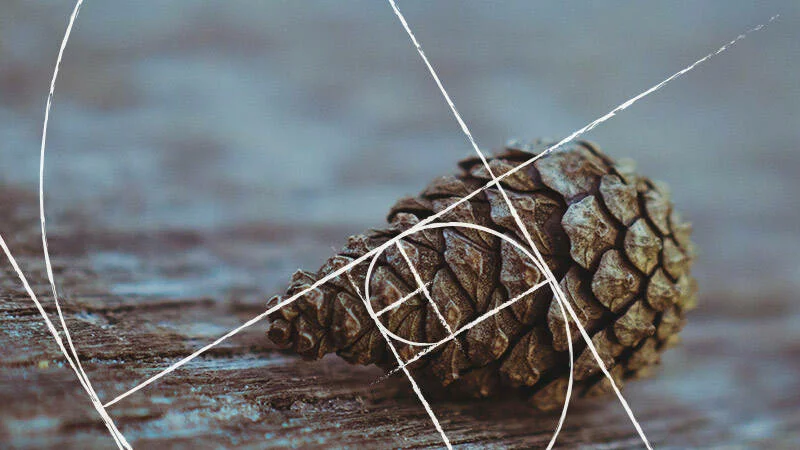

In the eighteenth century, William Paley formalized this intuition with the watchmaker analogy. If you stumbled upon a watch lying in a field, you would rightly conclude that it had been purposefully designed by someone. Only a fool would think that natural causes would be sufficient to engineer something so intricate. So too with the universe—it has an intelligent designer. At least that was the conclusion drawn by Paley, that “every indication of contrivance, every manifestation of design, which existed in the watch, exists in the works of nature.”William Paley, Natural Theology (London: William and Robert Chambers, 1837), 3.

The spirit of Paley was given new life in the Intelligent Design movement, headquartered at the Discovery Institute in Seattle. Beginning with groundbreaking works like Charles Thaxton, Walter Bradley, and Roger Olson’s The Mystery of Life’s Origin, Michael Denton’s Evolution: A Theory in Crisis, and Phillip Johnson’s Darwin on Trial, these intrepid thinkers set out to dethrone the scientific naturalism so dominant in academia and the wider culture.Charles Thaxton, Walter Bradley, and Roger Olsen, The Mystery of Life’s Origin (Dallas: Lewis and Stanley, 1984); Michael Denton, Evolution: A Theory in Crisis (Bethesda: Adler & Adler, 1985); Phillip Johnson, Darwin on Trial, (Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 1993). In time, this movement has grown into a positive research program built on the premise that intelligent causes are empirically detectable in nature, indeed that such intelligence is central to understanding the very meaning of biological life.

Not everyone is convinced, to put it mildly. Secular scientists are largely dismissive, but even fellow Christians strongly contest the scientific legitimacy of Intelligent Design. Mind you, they are skeptical not because they reject God as the Creator, the maker of heaven and earth. No, the issue is a theological disagreement, at least in part, specifically that divine providence should not—and in fact cannot—be submitted to a scientific test. The signs of creation and providence pervade all of nature, the critics say, and should thereforeOur goal is for these authoritative reflections to help the rest of us gain clarity on the issues—more light, less heat! not be narrowed down to alleged instances of “specified” or “irreducible” complexity. Beyond theology, the debate over “methodological naturalism” is only one of several philosophical questions about what should and should not count as legitimate science.

Hopefully this superficial overview is enough to indicate the significance of these debates and how the core issues are still very much with us. I’m therefore honored to roll out a new feature from the Creation Project—our “Areopagite” series. This fresh series aims to facilitate greater clarity on difficult or contentious areas of debate; each installment of the Areopagite will pose a controversial question and we will then invite a handful of respected scholars, from different perspectives, to respond. Our goal is for these authoritative reflections to help the rest of us gain clarity on the issues—more light, less heat!

Welcome, then, to our first installment with this question on the table: Is purposive, intelligent design detectable by the scientific investigation of nature?

Comments

Be the first one to make a comment!