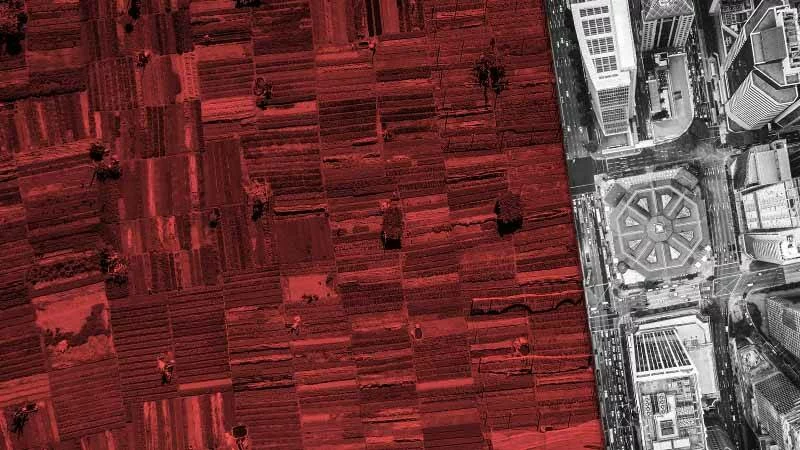

Since the massive social and demographic upheaval brought about by the industrial revolution, rural America slowly began to slip into the background of culture and society.There remains a great deal of discussion among sociologists and policy makers regard the definition of “rural.” For the purpose of this discussion I define rural as: “communities and towns with a population base less than 10,000 people, that are not in close proximity to an urban core, that exhibit characteristics of rural culture, and that are often (but not exclusively) economically and emotionally connected to the land upon which they live.” For further discussion see Glenn Daman, The Forgotten Church (Chicago, IL: Moody Publishers, 2018),30–35. As a result of the industrial revolution, with the focus shifting to the rise of urban centers with its opportunities for jobs and wealth, the population of America began a massive migration from rural communities to urban centers.

When the founding fathers first established a new nation, their vision was more or less an agrarian one. For the first one hundred and fifty years of the nation’s existence this remained true. In 1900, sixty percent of the US population still lived in rural communities. But beginning in early 1900s, the urban migration began, so by the end of the twenty-first century, rural America had become a marginal minority and was increasingly forgotten. As the power of the vote transferred to urban centers, so the focus of the politicians shifted to the urban vote. This urbanization of American society not only shifted the focus of governmental policy, it also shifted the focus of the church. As rural Americans became forgotten, so the rural church became neglected. Denominations and mission organizations began to focus upon the needs of the inner city and the church planting opportunities of the rapidly growing suburbs. Then, with the rise of the church growth movement with its emphasis on growth, market-driven ministry, and vision development, the rural church seemed archaic and dysfunctional. Here again, in an age where people measured effectiveness by size and programs, the rural church was forgotten.

Tragically, the forgotten church has become the neglected church. The divide between rural and urban encompassed a conflict of cultures and of worldviews, and the church, too, was caught in its sway. From politics and morality to the environment and economics, rural and urban residents often looked through different lenses.For an overview of the differences see Robert Wuthnow, The Left Behind: Decline and Rage in Rural America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018). This became true of the church as well. While urban and suburban churches focused upon vision and numerical growth, the rural church focused upon maintenance of traditions, community, and relationships. This is not to say that the rural church neglected vision and mission or that the urban church neglected tradition, community, and relationships. Rather, the rural and urban churches often have different priorities, and these different priorities are embodied in different forms.See further, Glenn Daman, Shepherding the Small Church (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel, 2008).[/post-annotation] Based on these differences, some view the rural church as old fashioned, driven by tradition, and dying. As one denominational leader concludes, “in North America most small congregations are small and remain that way because they are spiritually and organizationally dysfunctional.”Paul D. Borden, Hit the Bullseye (Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 2003), 5. For some, the answer then is not to send more pastors to rural areas, but to close small rural churches in order to form large regional “Wal-Mart” congregations.Leith Anderson, A Church for the 21st Century, (Minneapolis, MN: Bethany Book House, 1992), 59–60. But what, then, is rural America, how does this life situation impact the church there, and how might the wider body of Christ partner in ministry with our rural churches? These are some of the questions reflected upon throughout this series. In this piece, I’d like to more modestly provide a vignette of rural America and its church.

The Crisis of Rural America

For many, our perception of rural America remains frozen in the past nostalgia of Mayberry, where everyone attended white churches with white picket fences surrounded by green cornfields. But perception is often colored by false assumptions. As the population migrated out of rural communities and the focus shifted away from the rural communities and ministries to urban growth and suburban opportunities, rural communities began to crumble economically and spiritually. Rural America was becoming the new inner city, as sociologists often speak of it, a place plagued by massive outmigration, economic depression, rising crime, and an epidemic of drug abuse. Just as the crumbling of the inner-city lead to the anger, despair, and resentment, so now the collapse of the rural culture and way of life led to the anger expressed in recent elections.For a more in-depth study, see Wuthnow, The Left Behind. To understand the anger and resentment of rural people we need to delve deeply and listen and see what is happening in rural communities and the rural church across the nation. Robert Wuthnow did just this, determining “to understand what their lives are like, what they value, and how they arrive at their opinions about political candidates and government.”Wuthnow, The Left Behind, 3. In describing the anger in rural America, he concludes: “The moral outrage of rural America is a mixture of fear and anger. The fear is that small-town ways of life are disappearing. The anger is that they are under siege. The outrage cannot be understood apart from the loyalties that rural Americans feel towards their communities. It stems from the fact that the social expectations, relationships, and obligations that constitute the moral communities they take for granted and in which they live are year by year being fundamentally fractured” (p. 6). To understand rural America and the crisis that is occurring, we must go beyond the characterizations and nostalgic views and examine what is really occurring.

Poverty in Rural Communities

This begins by recognizing that rural America has become, in the words of Osha Davidson, the new ghetto, where poverty, economic hardship, deterioration of infrastructures, and outmigration have become an epidemic. As Davidson points out, “The word ‘ghetto’ speaks of the bitter stew of resentment, anger, and despair that simmers silently in those left behind. The hard and ugly truth is not only that we have failed to solve the problems of our urban ghettos, but that we have replicated them in miniature a thousand times across the American countryside.”Osha Gray Davidson, Broken Heartland: The Rise of America’s Rural Ghetto (Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa Press, 1996), 158. When we examine closely the economic wellbeing of people in rural communities, we find that not only are many rural counties experiencing poverty on par with the central city, but in many counties, it exceeds it, with some communities experiencing poverty rates approaching thirty percent.Davidson, Broken Heatland, 9. For a state by state comparison of rural and urban poverty see City and Rural Kids Count Data Book. (Baltimore, MD: Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2004) and Amy Glasmeier, An Atlas of Poverty in America: One Nation, Pulling Apart, 1960-2003, (New York: Routledge, 2006). The hardest impacted are rural children where there are more than twice the number (three million) of low-income white children living in poverty than in the central cities. Hit especially hard are Native Americans, where over fifty percent of children live in poverty.Jeanne Hoeft, L. Shannon Jung, and Joretta L. Marshall, Practicing Care in Rural Congregations and Communities. (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2013), 115. Furthermore, almost ninety percent of all the “persistent poverty” counties—those that have experienced poverty rates above twenty percent for the past thirty years—exist in rural areas.Richard E. Wood, Survival of Rural America: Small Victories and Bitter Harvests, (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2010), 17. See also Ann R. Tickamyer, Jennifer Sherman, and Jennifer Warlick, Rural Poverty in the United States (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017).

In contrast to the urban poor, the rural poor face two significant hurdles: First, studies spanning across several different decades consistently reveal that rural areas not only experience equal or higher poverty rates than inner-city areas, but they are more likely to remain persistently poor with fewer options and opportunities to rise above it. Second, rural communities have fewer resources (education, jobs, and government assistance programs). The most significant distinction between the rural poor and their urban counterpart is not the amount of poverty but the absence of options and programs to assist them in transitioning out of poverty. The point here is not to dispute who is the poorest, but merely to call attention both to the fact that poverty is a real problem in our forgotten rural communities and that it presents some unique challenges from our urban-biased responses to the problem

The Opioid Crisis in Rural Communities

It is now recognized by government agencies that rural America is in the throes of an opioid crisis.For more information on the rural opioid crisis, see USDA Rural Community Action Guide at https://www.usda.gov/sites/default/files/documents/rural-community-action-guide.pdf?fbclid=IwAR3sZ1b9GnAT9X8XV-4soWaaL1VApB4Bq95R9Cte5Y5ahjoewDZVwt7Y8A4 When surveyed, seventy-five percent of farmers and farm workers state that they have been directly impacted by opioid abuse.Rural Opioid Epidemic, Farm Bureau, https://www.fb.org/issues/other/rural-opioid-epidemic/ In October 2017, a survey of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reported that deaths from drug overdoses in rural areas have now surpassed drug overdose death rates in urban areas. CDC Reports Rising Rates of Drug Overdose Deaths in Rural Areas. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2017/p1019-rural-overdose-deaths.html But this is not just a problem of the young seeking a thrill. The CDC report that almost forty-four percent of opioid-related deaths in rural areas in 2015 occurred among adults ages forty-five and older.See https://www.asaging.org/blog/rural-older-adults-hit-hard-opioid-epidemic Yet only one in ten opioid treatment centers are located in rural America. For many isolated communities there is little help in dealing with addictions. This places greater focus upon the local church and pastor as the source of assistance for families dealing with addictions. But the rural pastor and rural church cannot deal with the crisis alone. They need to form partnerships with urban churches who can come along side of them and assist them in dealing with those struggling with this crisis.In response to this crisis, Rural Matters Institute and Rural Opioid Initiative are partnering together to develop a program for assisting rural pastors to deal with the opioid crisis in their community. For more information on the opioid crisis and the response of the rural church see www.ruralopioidinitative.com.

Racial Diversity in Rural Communities

The third challenge confronting rural communities and the rural church is the rise of racial diversity in rural areas. While it is true that rural communities still lag behind urban areas in terms of racial diversity, it is rapidly changing. While many Latinos are migrating to the urban areas, the majority are moving to rural communities where the Latino population increased in the 1990s by sixty-seven percent.David Brown and Louis Swanson, Challenges for Rural America in the Twenty-First Century (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2003), 58. With the growth of Latinos comes many challenges, one of the biggest of which is education. Latinos encounter high levels of segregation, dropout rates, and pervasive inequities in school funding.Brown and Swanson, Challenges for Rural America in the Twenty-First Century, 63. This is especially problematic for the child of migrant workers who frequently move with their families as they follow the agricultural They also are plagued by poverty, especially the colonias residents, who are regarded as the poorest of the poor, where twenty percent are characterized by extreme poverty.Colonias are rural unincorporated subdivisions along the United States-Mexican border. They are populated by predominately Latino residents and often characterized by substandard housing and poverty. There are an estimated 2,500 colonias housing communities in the United States.

African Americans make up close to eight percent of rural residents. And like their Hispanic and Native American counterparts, they too struggle with poverty, especially in the Deep South. Rural African Americans in the Deep South are some of the poorest in the country. Thirty-five percent of the nation’s poor and ninety percent of rural African Americans living in poverty, live in the rural areas of the Southeast.Brown and Swanson, Challenges for Rural America in the Twenty-First Century, 35. But the most overlooked people group are Native Americans. They are overlooked not only by society at large, but also by the church. Today there are over two and a half million Native Americans (about half living on rural reservations), with over five hundred recognized tribes, most of whom face chronic poverty and social deconstruction.

With the growth of racial diversity in rural communities, racism and race relationships are not just an urban problem. They are issues confronting rural communities as well. Having grown up on an Indian Reservation, I personally know the divide between the two communities (the Native American community and the White community). In some ways, the enmity has only grown deeper. With the increase of racial diversity the rural church not only needs to examine the gospel implications of reaching different people groups in our own back yard, but also what it means to adapt our own cultural expressions in order to reach individuals of a different culture, even as Paul did when he stated that he became all things to all men to win some (1 Cor 9:19–23).

Ministry in Rural America

As with rural America more generally, so with the rural church: If we are to understand the church in these places, we must move beyond nostalgia and superficial characterizations and attend to what is really occurring. And for beginnings, we should not too quickly assume that these communities are Christian communities. Quite to the contrary, rural America is now a mission field. In our understanding of rural communities, we have mistaken moral conservativism with authentic conversion and transformation. Nationally, thirty-four percent of American adults do not have any affiliation with a church.Roger N. McNamara, The Y-B-H handbook of Church Planting, (Longwood, FL: Xulon Press, 2005), 49. Except for the region of the Bible Belt, rural communities not only correspond to the national average, but exceed it in some cases. In the rural areas of the Pacific Northwest and the Rocky Mountain region, those who claim no religious affiliation exceed forty percent.Michele Dillon and Megan Henly, “Religion, Politics and the Environment in Rural America,” Carsey Institute, No. 3 (Fall 2008): 1. Especially forgotten are the Native Americans, a group of people in our own backyard, who remain virtually unreached. No less concerting, many in rural areas who describe themselves as Christian and claim affiliation with a church live without any genuine spiritual transformation.

The evangelical church has rightly focused upon urban centers and suburban communities. The masses that live in the city are in desperate need of the gospel. But this focus has wrongfully led to the neglect of rural communities. To reach North America with the gospel of Christ, both in our witness and our neighborly love, we need to not only look to the city, we must also look to the country. For this to happen we must not only rethink what it means to take the gospel into all the world, but we must also rethink what it means to contextualize the gospel—even for rural contexts. Moreover, for this focus to be sustained, we also need to have a clear, biblical understanding of what it means to be a church. Here lies the threefold purpose of this series and the conversations that our various books have independently intended to bring to our attention: (1) We need to develop a biblical view of a healthy church, one that exposes the various problematic assumptions of certain urban biases; (2) we must ask what the rural church has to contribute to our understanding of a healthy church; and finally, (3) we must also recognize the needs of the rural church. The rural church is facing challenges that will require partnerships with the urban church to help equip it to deal with the rising issues of racism, poverty, and drug addictions. To meet these new challenges we need to rethink how we do ministry itself in a rural context. It is hoped that this symposium on two important books will stir the conversation to that end.

Comments

Be the first one to make a comment!