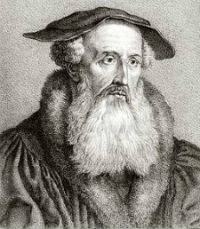

Heinrich Bullinger (1504–1575), Zwingli’s successor in Zurich, was a linchpin of Protestant communication ranging from England to Italy, Hungary to France.

His correspondence may have consisted of twenty-thousand letters, of which only twelve-thousand are extant. His Second Helvetic Confession (1566) became the definitive Reformed statement of faith, adopted by the Reformed churches of Scotland, Hungary, France, and Poland. In this passage from his sermon collection, the Decades, Bullinger draws out one of the key implications of Philippians 2:5-11: the doctrine of Jesus’ two natures in the unity of his person.

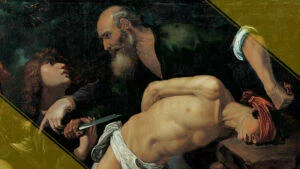

The same apostle says to the Philippians that the Son is “in the form of God.” But to be in the form of God is nothing other than in all respects to be equal with God in all things, to be consubstantial with him and so indeed to be God himself. For what it is to be in the form of God is clarified by the second clause. For it follows on: “he assumed the form of a servant.” This is expounded by what follows, “being made in the likeness of men,” that is to say being truly human, in no way dissimilar to all other men, excepting sin, which in another place is clearly expressed. And here he adds again, “And found in figure as a man.” Therefore, to be in the form of God is to be co-equal and consubstantial with God. For he adds, “He thought it no robbery to be equal with God.” For robbery is the unlawful taking away of someone else’s property.

By nature and in the proper manner, therefore, the Son is co-equal with the Father and true God. And this is the meaning of Saint Paul’s words: although the Son had the same glory and majesty with the Father, and could have remained in his glory, without humiliation, yet he preferred to abase himself, that is to say, take onto himself human nature, and throwing himself into danger, even unto death itself. For otherwise according to his divinity, he suffered no change. For God is unchangeable, and without variation.

Comments

Be the first one to make a comment!