Canto I

1.

The beginning of the Inferno and of the whole Comedy merits special attention because, like any good beginning, it prepares us for the whole rest of the work. Dante believed that literature (including, for him, history and philosophy) signified on both literal and allegorical levels, that is, both describes events within a narrative and points to realities beyond it. This purpose is immediately clear from the first lines:

Midway on our life’s journey, I found myself

In dark woods, the right road lost.

We still talk of “middle age” as somewhere in one’s late 30s to 40s, but when Dante speaks of a life’s journey collectively he invokes a specific concept of the universe—in this case a strategically literal rendering of Psalm 90:10—that already establishes the main symbolic frame by which he structures the Comedy. The poem is set in 1300, probably beginning the night before Good Friday (based on evidence in Canto XXI), which means Dante the pilgrim would have been 35—a conveniently solid set of numbers to the medieval mind. “Life’s journey” is already metaphorical (journey means “a day’s travel”), so “midway” encompasses both the visual image of a path and the temporal arc of an individual life.

A middle suggests a division— between the first and second halves of some event or the balance point of a scale, for which a decision one way or the other is decisive. Dante is about to relate an event that changed his life. This is a turning point, one which will change his orientation both to his past and to his future.

2.

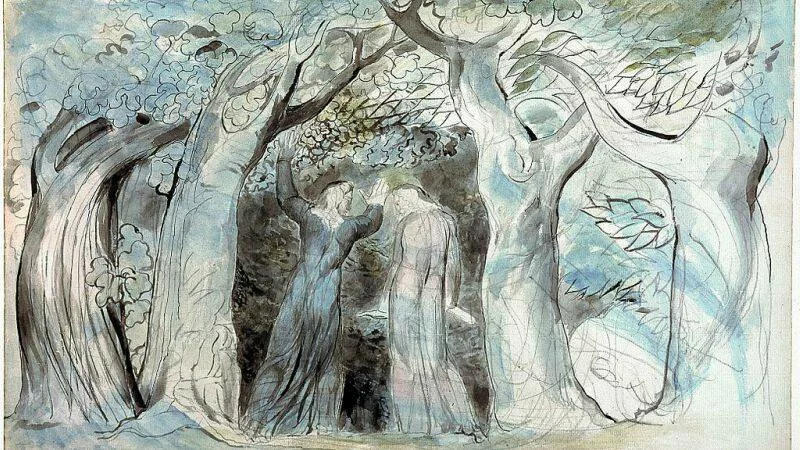

I’d guess dark woods have a universal quality, at least for the Anglo-European mind; they are the setting of many of our fairy tales and of medieval romances, places of magic and menace. From the many cross-section illustrations I’ve seen of Dante’s Hell, I used to imagine the pilgrim entering a cave and descending deep underground. As I reread it, however, I realize that he and his guide, Virgil, are certainly descending toward the center of the Earth, but they are probably not actually in a cave. The illustration in Pinsky’s translation helpfully lays out Hell topographically, so you can picture it as a large bowl with many terraces. Somehow being still outdoors makes it more distressing for me. It means Hell is closer to our familiar experience than one gets in the Greek sources. Kind of post-apocalyptic, perhaps, still somehow, mystically, continuous with our reality.

We shouldn’t overlook the significance of this continuity. Dante’s vision of entering Hell suggests not so much a literal place on the planet as a condition that co-exists with our daily lives. Read allegorically, straying from the right path won’t just eventually lead us to Hell—it could put us there in the present. But then, keeping to the path brings us closer to a Paradise that is to some extent continuous, though, as we’ll see, in an unusual way.

The degree of death’s sting will correspond to which afterworld kingdom we’re approaching in the present. Those of us living Kingdom lives now will not feel death as the last word on a human life. Those of us living in a Hell-on-Earth will likely find death much more menacing.

I write this having experienced two significant deaths in my own life since this summer. Both were believers; one had lived to a good old age, the other was taken in the middle of his own journey. We mourn Grandma Jean’s passing with little objection; she lived well and passed without great suffering. We mourn Brett’s life with a confusion of emotion; he, too, lived well, but he was taken from his family, friends, and a great career. Having the hope of eternity, however, means we can object to his death in the strongest terms and yet we can also take comfort in seeing him again and in seeing all pain and death redeemed.

3.

Dante explains a few lines later that his purpose is in part didactic, “to treat the good I found there.” That he bothers to justify himself for writing about Hell probably owes more to the epic tradition of declaring one’s purpose, but as a Victorianist, it reminds me of the problems critics raised with Gothic literature. Why write about these horrible things? It appears lurid or macabre. One might wonder whether you’re thinking on what is right, pure, lovely, and admirable (Phil 4:8). An image search for “Dante’s Inferno illustrations” will testify to the sometimes disturbing allure this text has had for the visual imagination.

But we also know there are two more books, that Hell is only the beginning of a longer journey culminating in Paradise. Just like we know that the hero will get out of trouble when we’re still in the first act of a film, we know there’s more story, that we shouldn’t prematurely conclude anything about this pilgrim until we travel with him through the whole journey he intends to recount.

One last observation for Canto I. When Dante finally encounters Virgil, he cries out to him, “You are my guide and author”—in the Italian, “my teacher and my author.” To separate out teacher and author suggests he means author in the emphatic sense of “creator.” We know Dante believes in guides, but we also know that for him God is the ultimate author of us all. The pilgrim certainly honors Virgil with this hyperbole, and there is probably some truth to the attribution, but Virgil is himself in Hell and is just a man, so we should pay attention to how the pilgrim’s thinking about himself and his guide develops.

Comments

Be the first one to make a comment!