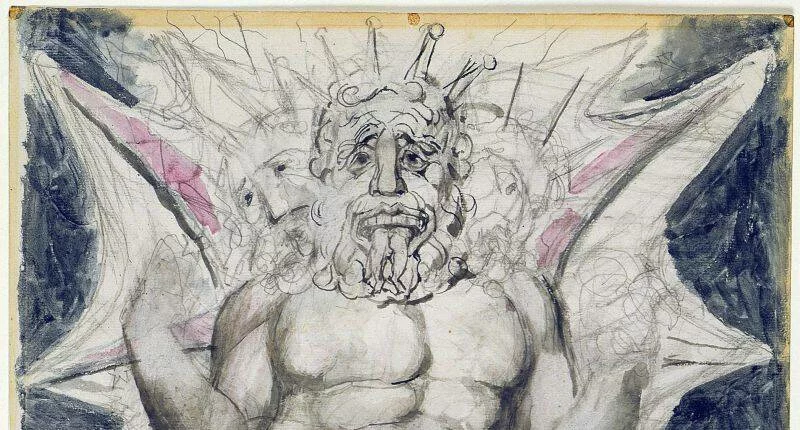

It has been a long, often bizarre trip, but at last we have reached the lowest point of Hell and the end of Dante’s catalog of the eternal wages of sin, Inferno. As I think about the Henry Center’s theme, The Sting of Death, it seems to me Dante has made a pretty extensive case for what that sting might look like not to those left behind but to the soul who suffers it.

The good news is that Dante and Virgil will come out the other side of Hell. Virgil will eventually return to Limbo, which is not the worst, and Dante will eventually return back to his life, purified and properly ordered toward the good. But the worst sinners are before us: the betrayers.

Betrayal is Totally Cold

We’ve seen plenty of the fire and brimstone version of Hell on the poet’s journey, though it was restricted to really only a few circles, partly because it does not always fit Dante’s contrapasso allegory and partly, I think, because Dante can think of more kinds of suffering than just burning. When we get to the lowest region of Inferno, though, we leave the heat and drama and dynamism of the upper circles and enter a cold, static world of ice.

I find this fascinating. In the darkest pit of Hell is a frozen lake of ice. Some souls’ heads are still free and they can speak, but some of them are trapped deep within, only visible as blurry colors, “like straw in glass.” It is the nightmare vision of eternity, perpetual sameness, discomfort, entrapment.

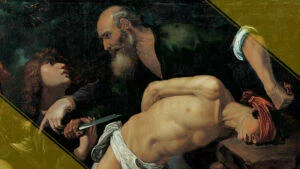

Why are the betrayers the worst of sinners? Judas probably offered Dante a model or cue; it doesn’t get much worse than sending God to His death. But we’ve already seen that the sins deeper down tend to concern abuses of the divine image in others, and betrayal is the most destructive to the dignity and glory of the other because it depends upon and turns against the other’s love. I cannot betray you unless I have earned your trust; I cannot hurt you deeply unless you first love me deeply. As anyone who has suffered betrayal knows, it’s a wound that does not quickly heal.

Dante finds betrayal so monstrous that, shockingly, he imagines that the souls of betrayers actually descend into Hell before their bodies die. The body continues to act under possession so that, to the living, the betrayer has become literally demonic.

Here Dante extends the image of Judas’s betrayal in John 13:27, “As soon as Judas took the bread, Satan entered into him” (NIV) If Judas, why not other betrayers? Note, too, the poetic inversion of John’s gospel. Satan enters into Judas, and then Judas’s soul spends eternity in Satan’s mouth.

The Other Side of Hell

Finally, follow the allegory through to the end: the way out of Dante’s dark night of the soul has always been to descend through the darkness, sin, and suffering. Now we arrive at the ultimate depths of that process, the emblem of all sin, Satan himself, and the way out is to grab onto him and invert yourself so that you stand upright while he is rightly upside-down.

I love, here, the geographical description of Satan’s fall from Heaven. The earth so abhors and fears him that it gives way on either side, piling up on either side of the planet to create the Mountain of Purgatory in the south and some unnamed topography in the north, while Satan gets lodged in the middle.

Virgil explicitly says the cavity in which they then stand was created by this dislodged ground, but I also imagine that Hell was created on the other side by the same process. Satan’s crime, then, creates both Hell and Purgatory, both the place of punishment for sin and the (metaphorical, minimally) means of emerging out of them.

As I’ve said, it’s hard for me not to picture Inferno as a cave, and part of this certainly owes to the way the final line of this canticle feels like such a relief from the claustrophobia of the poem. Suddenly, instead of looking down deeper into the darkness, we can look up, see the stars, feel the dawning sky opening above us. Stars still symbolize for us a world beyond, but for Dante they represented the rational intelligence behind and within the cosmos. The chaos of Hell is behind; we are back in a world of comforting order.

The challenge for Dante the poet, now, will be to show us not only purification but also eternal beatitude in a compelling, non-clichéd way.

Comments

Be the first one to make a comment!