A Humble Petition (Canto IX)

What better way to enter Purgatory than with an act of humility? This may seem obvious, but we’re prideful people who don’t generally even appreciate how prideful we are. Think about how easy it is to confess to a variety of Christian “struggles,” to go on missions trips or attend Christian club events, and to feel like you’re doing pretty good at the Christian thing. In the first level of Purgatory, Dante slowly and gently takes this apart by showing us how our pride might look to God and what God really values.

Up through canto VIII, we’ve been skirting the base of the mountain in the Ante-Purgatory, where some souls have to spend several lifetimes getting adequate distance from their earthly lives in order to be ready even for the journey up the mountain, which is itself preparation for Paradise.

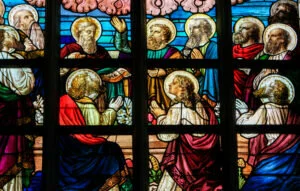

Everything feels very laden with allegorical significance as Dante and Virgil approach the stairway guarded by the angel of God in canto IX. The stones and their colors suggest refinement (the polished marble), purification (the rough purple stone), and sacrifice (the blood-red porphyry), and there is a ritual quality to the way Dante throws himself on his knees, beats his breast three times, and makes his plea, as well as in the way the gatekeeper places the seven P’s on his forehead. Later Dante acknowledges that his verse has had to become more elevated as his subject has. We’re drawing slowly closer to God on a journey of purification, so we should perhaps not be surprised to find more formality and, indeed, more discipline.

To my sensibilities there’s something rather indecent about Dante’s display of humility, to be honest. I’m not one to make a spectacle of myself or draw attention to myself in any way. I don’t often raise my hands when I worship. I’m not much of a crier.

I’m not sure which combination of origins made me this way. I suspect it’s a certain amount of modernity, a certain amount of Midwestern-ness, and a lot of Britishness, though I know there are plenty of other ways one could get to here. And some is probably an innate pride. Some are prideful about how expressive they are; some in how aloof. Still, when I read scenes like this, I try not to just say, “Oh, this is some medieval Catholic penance stuff.” That would be taking the easy way out. I have to remind myself that the stakes are pretty high: this is not just the pilgrim’s path back to his life—it’s his path from that life back to God. Maybe a little public humiliation is worth it.

Green is the Color of Your Fading Renown

In earlier cantos green was emphatically the color of hope, so it strikes me as odd to find the prideful Omberto associating green with worldly fame:

Some of Dante’s similes are pretty straightforward—surprisingly so, even. But this one is quite a bit more complicated than that. He emphasizes the color green, but he adds a temporal dimension that helps draw in tactile and perhaps even olfactory associations. When I imagine the grass fading, I see not just the green but the way it waves in the wind, the pliant blades that bend and curl. After a dry summer the grass becomes yellow and stiff, it even crunches under your feet.

And here’s where one more part of the simile comes in: the same sun produces both the fresh, green grass and the dry, yellow grass. The Purgatorio associates God with the sun; this is why the penitents cannot climb the mountain at night, when the sun is not there to light and warm their way. Omberto’s simile, then, doesn’t just make a point about the fickleness of politics or society but suggests God’s omnipotence and his ability to raise up and tear down.

Green, then, can suggest the ephemeral, or perhaps, at best, the cycle of the seasons, all under the will of Heaven. Not exactly hopeful in the conventional sense; it means we cannot count on our own skills and charms to prosper. But maybe there is still hope just in our submission to God’s omnipotence. Just because our lives can take unexpected turns, just because no state of affairs can be permanent, the fact that an almighty creator oversees us and has us in his care offers us hope that we can survive the turns of Fortune’s wheel because our true home and treasure is with a more reliable landlord.

The Humbled

And the haughtiness of man shall be humbled,

and the lofty pride of men shall be brought low,

and the Lord alone will be exalted that day.

—Isaiah 2:17

As in Inferno, a logic of contrapasso dominates Purgatorio, so that the proud are literally brought low by huge boulders they carry on their backs. In Inferno, the pilgrim’s sight of these souls would be accompanied by moaning and sighs and that feeling of menace that pervades Dante’s hell. The whole tone of Purgatory, though, is lighter, and the souls don’t boast or complain but rather ask to be remembered by the living so to speed their way to Paradise.

Think about that. The souls in Hell wanted to be remembered to the living for their deeds or their tragic fates— ultimately narcissistic reasons. The souls in Purgatory want to be remembered for their sins because only then will they receive the prayers that will draw them to God. There’s some humility for you.

And still we see evidence of God’s eagerness to pardon. At the end of canto XI, Dante the author places the ambitious and prideful Provenzan Salvani among those already ascending, though he had recently died and not spent his full term in Ante-Purgatory. Oderisi da Gubbio, his interlocutor, responds:

He advanced to this level for one act of deep humility: begging in the square for his friend’s ransom.

The First Purification

There was no real progress in Hell, just progressively worse sins the deeper Dante and Virgil traveled. In Purgatory, the souls progress upward. In Ante-Purgatory, they learn to leave the cares of their previous life behind and their desires are, slowly, rightly ordered. Then they progress to that level of the mountain where their dominant sins must be purged.

The P’s placed on Dante’s forehead (for penance, presumably) mark the progress of this living person through each level of Purgatory, the bodily record of his own need to be purified through this journey. As he prepares to exit the first level, the prideful souls, the guardian angel strikes him on the forehead with its wing, and one of the P’s disappears. We can expect something like this ritual to repeat with each ascent, and while it is formal and programmatic, it reminds me of James K. A. Smith’s recuperation of liturgy as the way our whole beings are trained to desire God.

If this ritual doesn’t, perhaps, feel significant now, I expect it will gain in significance for the pilgrim, at least, as he ascends and learns to appreciate the beauty of the purified soul. And note again how the whole ritual humbles the pilgrim and places him at the mercy of the gatekeepers. No room for pride in Heaven.

Comments

Be the first one to make a comment!