You’ve probably seen the videos for Dove’s Campaign for Real Beauty. They usually begin with women describing their appearance as inadequate or inferior before another woman or a man or an artist do or say something that reveals that, in fact, others see them as quite beautiful. The videos are well-made, sincere, and legitimately powerful in their portrayal of personal and social discovery.

Each new release of these videos proves to be a stressful time for me to be online, however. I have a diverse enough group of friends that I’ll invariably have some number of them sharing the video because they found it moving while some other number shares the one or two popular articles criticizing it because of a perceived problem in its message to women.

The voices who really, truly believe beauty is little more than a social tool used by patriarchy to oppress women are probably a significant minority, but they are web-savvy and therefore loud. They are also often intelligent and passionate, so while I chafe at their knee-jerk instincts to see ideological oppression everywhere outside their own hearts, I don’t want to make the mistake of presuming I have nothing to learn from them—just as I’ve been seeking to learn from this medieval, Italian, Catholic poet. Social ideals of beauty surely have been used to oppress women. They are arguably being used against men, now, too.

The Power of the Gaze

Canto XIX opens with an unexpected commentary on beauty. Dante has a kind of waking-dream or vision of a siren, a figure from Greek mythology who is both beautiful and unattainable and whose singing overcomes sailors’ wills and draws them to shipwreck themselves. Famously, Odysseus only survived hearing them by plugging the ears of his crew with wax and tying himself to the mast of his ship. They are, then, symbols of dangerous female beauty, a danger that is part nature (their physical beauty) and part art (their song).

So although it is a fact that the very best customized essay writing service may charge the least, that will not mean that the corporation should of necessity be the greatest in the caliber of the services they offer. Don’t forget that they are trying to sell you a product. If you are investing in a service that you don’t use, then you definitely should assume the support to be inferior with regard to quality.Some of the very most famous known companies have many services for their clients to pick from. You are able to find them with regards of the type of companies, including samples, tutorials, text to speech, surveys, and much far more.

Along with having a wide variety of services and products, these companies are likewise a number of the best with regard to customer essay writer services.Don’t permit that you got down their price to just function as kick off point. As an alternative, consider getting some reviews from existing clients so as to receive yourself a clearer concept of the way that they feel about the ceremony. All of these factors together are definitely going to assist you to get a really great idea of which custom essay writing services offer the very best for the demands.

You don’t have to be well-versed in feminist theory to perceive the problems with this image—especially as a female. As a male, you only have to know maybe two females and have a half-decent awareness of your own faults to see that one wouldn’t want to presume all women were like the sirens.

One common criticism of discussing a woman’s beauty is that it identifies a woman’s value with her physical appearance, which she has limited power over, rather than with any personal qualities, which she has much more power over. Another is that it depends on an equivalence of beauty with goodness and ugliness with evil—an age-old dichotomy that has power but also obvious limitations. Whether these are fair or right or not is beyond my scope, here.

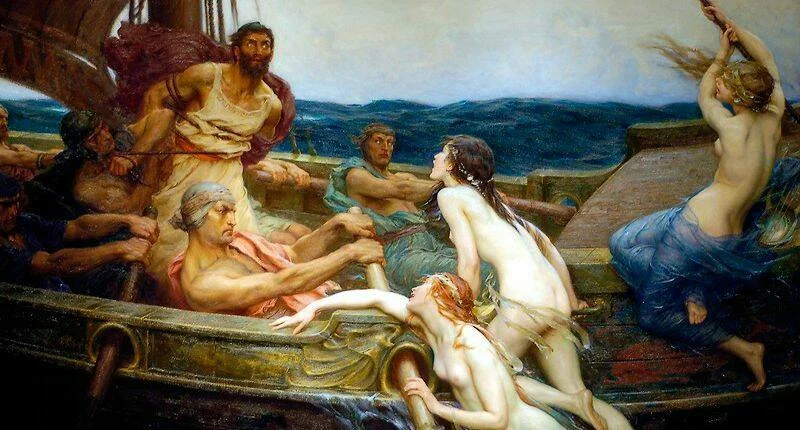

I want to focus on how Dante, who obviously worked from medieval concepts of beauty, still manages to flip the dynamic around. He begins by re-imagining the siren. She first appears not as a beauty but as a disfigured crone—and why not? The myth says you hear them first, and no one has gotten close enough to see them and live. H. J. Draper’s painting (featured above) is typical of the tradition in ignoring the aurality of the myth, imagining the sirens visually, and placing their usually nude beauty in the foreground of their picture.

Dante creates some space between the beauty of the song and the beauty of the singer. It is only after the pilgrim stares at her for some time that she transforms into the beauty she is purported to be, “the color / love most desires,” as he puts it, connecting beauty with the gaze that perceives it. In fact, Dante emphasizes that her beauty is not innate nor a function of sorcery but the result of his gaze:

This gaze even smooths out and beautifies the siren’s speech so that the pilgrim is captivated by her, as in the myth, and requires the aid of St. Lucy and then Virgil to come to his senses.

What’s going on here? Why this transformation of the source myth? Why this image of sexual perversion in the ring of avarice?

The episode suggests it is not feminine charms that lead men into sin but a sinful way of looking. We might think of Christ reframing adultery not just as a physical act but as an internal desire. Strikingly, the problem with the gaze isn’t that it desires but that it distorts what it sees so that it desires what is in fact undesirable.

Okay, so Dante stays within the visual beautiful/good vs. ugly/evil discourse, but this dichotomy has power because it recognizes that beauty is a good (or maybe we should say it is a good), that it exists objectively even if we sometimes mistake it for something else. Moreover, it strikes me that the association is more problematic for those who deny transcendence than for those who do not. After all, it really comes down to a visual literalization of a spiritual truth, that the good soul is beautiful and the wicked soul distorted, grotesque—ugly.

Which is Dante’s point. The perverse male soul will mistake what is spiritually ugly for what is truly beautiful, will in fact ornament the ugly in his mind until he convinces himself it is beautiful. This is why the vision occurs among the avaricious, those sentenced to lie in the earth they so treasured in life. The avaricious souls mistook worldly goods for ultimate goods, desired to amass what was temporal and fading instead of what was eternal and unchanging. They heard the siren song of gold or possessions or power (or even beauty, perhaps) and persuaded themselves those things had more than superficial attractions.

Virgil rescues the pilgrim from this vision by tearing the clothes off the siren, revealing “her whole paunch and all below,” which actually wakes him up “with the putrefying stench.” It’s rare to get olfactory images like that, but when you do, as here, they can be forceful. Virgil reveals the true spiritual nature of the siren, and it shocks Dante back into reality.

For Those of Us Not Inclined to Visions

Unfortunately for most of us guys, we’re surrounded by a world that thrives on the illusion and doesn’t want to permit us a view of the reality. Worse, our culture builds its illusion of the good on the foundation of real goods: finely crafted clothes or gadgets, beautiful bodies, nourishing and pleasing food. It’s not wrong to find Kim Kardashian beautiful, after all, or to admire the latest iPhone—it’s just wrong to believe that that’s all there is to enjoy, that the good life is following the right people on Instagram, eating at the right places, and wearing the right clothes.

Or thinking the right thoughts? Perhaps that’s more along the lines of a sin of pride. Those who scorn the Real Beauty videos and the women in them may want to consider heading back down the mountain to the ring of souls bearing large boulders on their backs, brought low, at last, by their common sinfulness with others. Surely we need a richer concept of beauty in our culture, and Dante teaches us that it’s not beauty that’s at fault, but our own perverse imaginations.

Comments

Be the first one to make a comment!