At the summit of Purgatory: Eden, the Earthly Paradise, the state of original innocence preserved as the field of rest before ascending to the gates of the heavenly Paradise. We’ve already had a climactic trial by fire, where can the story even go from here?

A Second Climax?

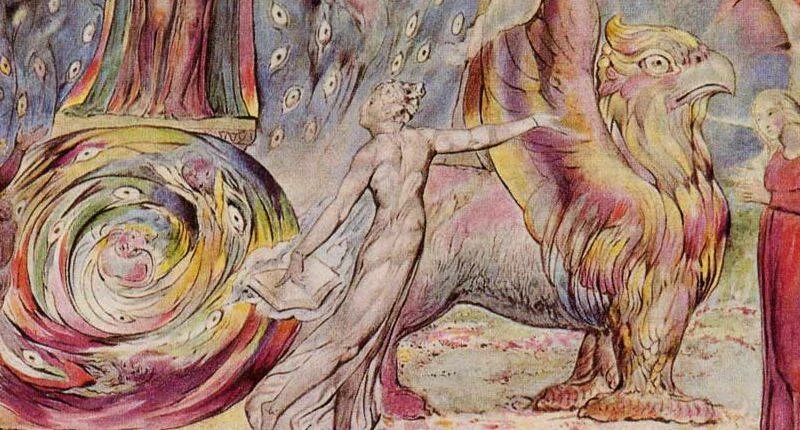

To perhaps the weirdest imaginable place, at least for a modern reader: a grand pageant featuring the books of the Bible and a Griffin—and a seemingly extraneous climax in which Dante has to jump through some more hoops.

If you’ve read any medieval literature (and you should, really), this won’t seem so entirely strange. Or maybe you’re familiar with the rude mechanicals’ play at the end of A Midsummer Night’s Dream or the wedding pageant in The Tempest. Pre-modern audiences seemed to like getting a little ceremonial set-piece thrown in with their narratives.

The Medieval Penchant for Ritual Allegory

Part of the idea—in the case of allegory, anyway—is that some truths cannot be represented directly to the human mind, so the artist has to transform them into images—figures, characters, animals, objects, events, whatever does the trick. Any time your pastor uses a movie clip to illustrate a point, he or she is participating in this tradition of seeking concrete figures to embody abstractions and present them to our imaginations.

If these allegories feel funny today, it’s because they seem so ad hoc and ceremonial. It’s awfully convenient that the pageant should show up just when the pilgrim needs it to, right? At the same time, the theatricality of it all, it seems to me, should suit an age obsessed with the “meta.” That’s as may be, I suppose.

What’s important, I think, is to try to let the pageantry do its work on you. You’ll start to see how the paradeThe meaning is in the ceremony itself. gathers the major touchpoints of the faith together—not so much in terms of how they actually work in our lives but more in the way of an aid to memory or an accommodation to earthly understanding. The meaning is in the ceremony itself. I had reason to think of this at a recent wedding, which is a highly ritual event. As with any rite, you can feel how something sacred occurs just in the finite words and actions.

A Brief Theology of Allegory

There’s actually an interesting moment that speaks to this in the excerpts of Aquinas in Esolen’s appendices. Aquinas is trying to deal with the difficulty of understanding why God would make it in the nature of a soul to be joined to a body, since bodies understand only through images, while souls by themselves can understand things “simply.” Aquinas determines that “the perfection of the universe requires various grades of being,” probably because such a diversity would reflect the plenitude as well as the order of God.

But think about what he’s saying, then. Humans, as embodied creatures, must have a way of knowing suitable to them and to their place in Creation. The logician in him is perhaps a little peeved that our knowledge is as far removed from God’s as it is, but the theologian in him recognizes a rightness and perfection to it. And on this side of the Reformation, anyway, we can say that it’s remarkable how much grace and beauty are possible in a world of sensory images.

And I find the Griffin, for example, a fascinating way to appropriate the ancient world allegorically. A noble, yet terrifying creature, the Griffin aptly embodies the dual natures of Christ in a physical representation—moreso even than the beloved Aslan, who was noble and terrifying but still just a lion.

Be Careful What You Wish For

At the same time that images can be helpful, Beatrice accuses Dante for loving the wrong images, saying it was for that she arranged his whole journey through the spiritual realms:

As a lover of beauty, this is among the most serious of charges. It’s easy to confuse what we perceive as embodied creatures with what is most true. I think this is as true for scientists as for artists, the former just emphasize the repeatable and mechanical while the latter opt for the unique and experiential. I do think we can recognize in beauty the real shining through of grace, but as the prohibition against idols warns us, we should not mistake the object that allows grace to be made visible for the source of that grace. It would be like worshiping a reflection in a mirror when person (of God) himself was right beside you.

It’s in this sense that Dante experiences his former desires as “enemies,” distractions from the best things. So a child’s love of shiny objects makes him prefer a handful of coins to a twenty-dollar bill.

Just More Hoops?

But what’s the point of this when Dante has already been through Hell and Purgatory and been declared purified and therefore truly, profoundly free?

Obviously, God doesn’t ask us to just jump through hoops to demonstrate our obedience or love, though he may ask us to do things more for our sake than for his own. I read the accusation, his confession, and then his passage through the rivers as a final seal on the process achieved throughout the canticle. If it feels like another climax, that’s because of its gravity, but in many ways it is the culmination and celebration of his spiritual journey.

It is also a final cleansing. His sympathetic purification didn’t remove his history of sin, it only destroyed its power in his life. Now he can be cleansed in the river Lethe and restored in the river Eunoe and finally taken into the presence of his soul’s great love.

Dante leaves us with the wonderful image of himself reborn as “a new young plant appears / renewed in every newly springing frond.” That is, still essentially himself, but fresh and young as if remade, just as a perennial’s spring growth is continuous with its original seed yet new and newly fruitful.

Comments

Be the first one to make a comment!