Proper Caution

The Paradiso feels like the riskiest book to read, much less write about. To begin with, we have only enough information about Heaven to spark lots of speculation, much of it pretty fanciful.

Mark Twain skewered pious visions of Heaven by pointing out that most men he knew don’t act like they’d even want to go there. Why, for instance, would someone want to spend eternity singing when he didn’t like to do it for half an hour every Sunday?

We could extend that logic. What if I don’t want to play a harp or a tambor? What my cousin or grandfather isn’t there?

For me, the smarmy images of Heaven I grew up with raised a very disturbing question: What if I’m bored by all this cloud-ensconced eternity?

I wondered the same about Dante’s poem. What if it’s boring? What might that mean about my heart, the things I truly take pleasure in? Better to persist in pleasant fantasy than be brought by disappointment to a cold reality, right? And here I was worried about reading Purgatorio.

Imagining Heaven

Twain’s (and my) irony aside, most of these questions betray bad theology and a deficit of imagination. The self-sufficient God who creates from nothing can certainly figure out ways to keep his people entertained and happy in his presence. In fact, if we understood the major theme of Purgatory, then we’ll also know that he will purify our desires so that we will take perfect pleasure in his presence, just like we take pleasure in the signs of his grace and love in this life.

Dante wants to help us envision the profound order at the heart of the cosmos.But remember that Dante doesn’t describe Hell or Purgatory for the purpose of helping us plan our retirement to the Afterlife. He wants to reveal the nature of sin, in the first case, and to reorient our desires, in the second. In his Paradise, Dante wants to help us envision the profound order at the heart of the cosmos. He wants us to perceive its beauty and wonder, and thus to perceive the beauty and wonder of its Creator.

Specifically, says Esolen in his introduction, this cosmos must answer the human problem of justice (fallen humanity’s accountability for its sins), and Dante’s answer reconciles divine love with human freedom via Christ. That’s a tall order for anyone, and thus good reason to be wary.

Calling for Help

Dante opens with an epic invocation, that is, calling upon some appropriate muse to guide his words as he attempts to narrate fanciful and strange events. It’s a convention that signals both the poet’s modesty (“I’m inadequate on my own!”) and his authority (“The gods are guiding my pen!).

Here, Dante calls upon Apollo himself, the god of poetry and a metaphorical stand-in for Christ, asking only enough “virtue” so that he can “make manifest a shadow of / the blessed kingdom sealed upon my brain” (I.23-4).

That’s pretty good invoking.

And it reminds me that, in the same way, I as a reader can call in faith upon God to guide my reading, as I should with any text from which I hope to profit and toward which I hope to show hospitality. At the end of the day, if I don’t like Paradiso, it doesn’t reflect on Heaven itself, just on Dante’s poetry.

But I already have plenty of reason to trust that Dante can pull this off. The previous canticles were truly marvels of the theological and incarnational imagination. Furthermore, if I can keep Dante’s design regarding humanity’s freedom, God’s love, and Christ’s mediation in mind, it will provide a frame or lens through which to understand what promise to be strange events, indeed.

Out of the Silent Planet, Sort of

It’s fortuitous that I began reading C. S. Lewis’s space trilogy back in April, as Lewis is up to something very similar to Dante in them: an attempt to demonstrate the divine order of the cosmos via the imagination. Lewis differs not only in using prose fiction and in his choice of the sci-fi genre but in the fact that he’s using the heliocentric model of the solar system.

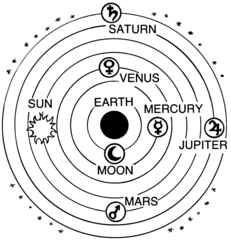

Dante maps the Christian afterlife onto the prevailing Ptolomeic model, which if you’ve never seen is a geocentric system wherein the planets orbit Earth on invisible spheres. This model provides spiritually provocative symmetries despite its cosmological errors.

I only bring it up because Dante and Beatrice travel Paradise via something like flying or assumption from Earth to the succeeding spheres, beginning with the moon. They’re literally flying through space.

I only bring it up because Dante and Beatrice travel Paradise via something like flying or assumption from Earth to the succeeding spheres, beginning with the moon. They’re literally flying through space.

This is before airplanes or even hot air balloons, so it’s not clear what flight looked like to a late-medieval mind—not to mention space. No doubt to us CGI-soaked readers the image of them floating upward would lack a certain visual dynamism, but as long as we retain the sense of peace and safety, I don’t think it would hurt to let yourself imagine whatever helps you. Maybe some kind of racing dimensional tube,or even something like a transporter.

As long as we don’t picture space as the black nothingness we’re used to since the 60s or so. Space for Dante, or more properly “the heavens,” is full of light and energy such that they are literally drawn or lifted upward by it, it becomes a medium for travel, not just a distance or gap (think about our word for it: “space”).

Lewis’s description of space in 1931’s Out of the Silent Planet probably owes something to the medieval picture, so it’s helpful in trying to get into Dante’s brain in these passages:

the stars, thick as daisies on an uncut lawn, reinged perpetually with no cloud, no moon, no sunrise to dispute their sway. There were planets of unbelievable majesty, and constellations undreamed of: there were celestial sapphires, rubies, emeralds and pinpricks of burning gold; far out on the left of the picture hung a comet, tiny and remote: and between all and behind all, far more emphatic and palpable than it showed on Earth, the undimensioned, enigmatic blackness.

[. . .]

the very name “Space” seemed a blasphemous libel for this empyrean ocean of radiance in which they swam. He could not call it “dead;” he felt life pouring into him from it every moment. How indeed should it be otherwise, since out of this ocean the worlds and all their life had come? He had thought it barren: he saw now that it was the womb of worlds, whose blazing and innumerable offsprint looked down nightly even upon the earth with so many eyes. . . . Older thinkers had been wiser when they named it simply the heavens.

We should picture Dante and Beatrice ascending through some such vibrant, abundant medium.

They are, after all, approaching the very throne of God, and God is not the god of mere “space.”

Comments

Be the first one to make a comment!