No one said improvisation is easy.

It requires the toys to place strong faith in their owner. And at times what Andy’s toys see doesn’t convince them that their faith was well-placed. Toys—like people—are visual creatures; they need evidence. In the case of identity this is an especially high calling. It’s easier for Andy’s toys to understand their identity in relation to what they see—stuff that they or others have.

What Woody’s Eyes Have Seen and Declared

When Buzz first arrives on Andy’s bed, Woody doubts his own significance because he doesn’t have as much stuff—gadgets and abilities—as Buzz. Mrs. Potato Head demands respect from Lotso because she has “over thirty accessories.” After Buzz finds out that Buzz Lightyear is fictional and that he is only one of many Buzz Lightyears, he places his confidence in what he can see: “Don’t you get it?!” Buzz protests pointing to his feminine hat and pink apron (given to him by Sid’s sister, Hannah), “You see the hat? I’m Mrs. Nesbit!” Woody agrees to leave Andy and his toys, choosing to go to a museum where he’ll never be played with, because on an old television show he was “the star . . . and there was all this merchandise. Buzz, I was a yo-yo!” The first two examples are misinterpretations of physical objects; the second two are false memories—Buzz never was a space ranger, and Woody never was a television star.

In each film there are numerous examples of the toys’ error that faith comes from seeing. Toy Story 3 provides one of the more compelling instances. The plot of Toy Story 3 spins out of control when Andy’s toys see themselves placed in a trash bag and then see themselves on the curb by the trash. These acts of seeing cause the toys to deny their memories of who Andy is and what he does for and with them. But they did not see how they got from Andy’s room to the curbside. Woody did. Nevertheless Andy’s toys don’t trust Woody’s testimony, instead they rely on the weight of deductive reasoning. Andy put them in a trash bag; he doesn’t want them anymore. And so the toys proclaim to Woody that they have a plan: Daycare.

“Daycare?!” Woody shouts, “What? Have you all lost your marbles?!

“Didn’t you see?” Mrs. Potato Head protests, “Andy threw us away!”

“No! No, no, no! He was putting you in the attic.”

“Attic?” Mr. Potato Head says suspiciously, “So how’d we end up on the curb?!”

“That was a mistake! Andy’s mom thought you were trash.”

“Yeah!” Hamm interrupts, “After he put us in a trash bag!”

“And called us junk,” Mrs. Potato Head adds.

“I know it looks bad, but, guys, ya gotta believe me!”

“Sure thing, ‘College Boy’!” Mr. Potato Head mocks.

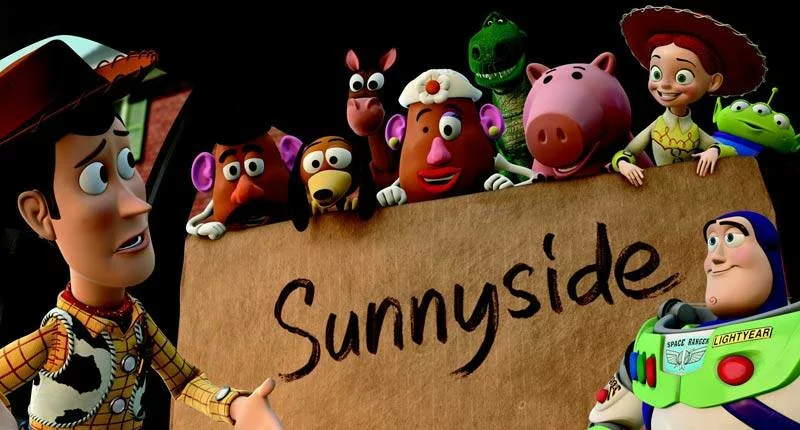

Sunnyside (and its underside)

Even though they didn’t actually see what happened, they refuse to trust Woody who actually did see what happened. At Sunnyside the roles are reversed but with the same result. Sunnyside looks good. “Woody, it’s nice!” Rex pleads, “See, the door has a rainbow on it!” Woody admits that Sunnyside is nice, but, remembering whose name is on his boot, he knows they need to go home. The others, however, have forgotten about the name on their feet and trust what they see. Andy’s toys soon learn that appearances can be deceiving; they are actually in a prison.In fact the animators visited a prison to design the scenes for Sunnyside. Notice, for example, that Andy’s mom is buzzed into the daycare. See Charles Solomon, The Art of Toy Story 3, 88-111.

After Buzz has been nabbed by Lotso and his thugs, Mrs. Potato Head reaches her eye out under the Caterpillar Room door to see what’s going on. She sees Andy! (Her other eye is still under Andy’s bed.) Everyone wants to know what he’s doing; they miss him. “Okay, Andy’s in the hall,” she tells them. “He’s looking in the attic. Wait, there’s mom. Why is he so upset? . . . Oh no! Oh, this is terrible! He’s looking for us! Andy’s looking for us!” Sad, angry, and confused the toys want to go home. They realize Andy did want them in the attic; Woody told them the truth—but they didn’t believe him. Andy’s toys are guiltstricken. But when Woody returns to get them out of Sunnyside he doesn’t fault them. “Oh, Woody, we were wrong to leave Andy,” Jessie admits. “I . . . I was wrong.” Woody responds, “No, no. It’s my fault for leaving you guys. From now on, we stick together.”The folks at Mockingbird emphasize that repentance and defeat build the climax of the Toy Story films. See Brewer and Zahl, eds., The Gospel According to Pixar, 55.

The Toy Story Gospel & Beyond

So faith comes from hearing (Rom 10:17). The toys should have listened to Woody, but Woody—as the local prophet—should not have abandoned his flock. Prophets must continue to promulgate their messages regardless of people’s responses. “We must not rashly abandon our duty because of so many people’s ingratitude,” Rudolf Gwalther, Zurich’s third lead pastor during the Reformation-era, warns, “instead . . . tolerating this evil with gentleness we must teach those who resist—in case God grants them repentance to know the truth and come to their senses and escape from the devil’s snare.”Rudolf Gwalther, In Acta Apostolorum per Divum Lucam descripta homiliae CLXXIIII (Zurich: Christoph Froschauer, 1557), 201v; citing 2 Tim 2:25-26; cf. Esther Chung-Kim and Todd R. Hains, eds., Acts, Reformation Commentary on Scripture New Testament 6 (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2014), 238. Woody can’t compel repentance; it must arise naturally. He needed to continue to tell them and to show them how to remember correctly. And Woody’s flock should have remembered who Andy has been to them and trusted in that; things aren’t always as they seem.

“Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed” (Jn 20:29).

Comments

Be the first one to make a comment!