Over 20 thousand street children, most of them orphans, roam the streets of Kinshasa. In response to the biblical call for God’s people to care for orphans, an organization of Congolese pastors led by Pastor Abel Ngolo called Equipe Pastorale Aupres des Enfants en Détresse (Pastoral Team for Children in Distress), and in partnership with Bethany Children’s Trust, works to care for the street children of Kinshasa.

The challenge is that these pastors have learned that roughly 80 percent of these children are on the street because they were accused of harming others through witchcraft. That is, according to the charge, these children have powers that have brought great harm to others. Thus Congolese Christians sometimes struggle between the biblical command to care for the orphan, and the perception that rather than these children being powerless, vulnerable, and innocent, they are in fact dangerous, powerful, and malevolent witches, causing other people around them to be vulnerable.

An Occasion for Pastoral Feedback

It was with this as a backdrop that Equipe Pastorale Aupres des Enfants en Détresse organized a conference on “Children Alleged to Be Witches” with several invited speakers: Opoku Onyinah, Andy Alo, Timothy Stabell, and myself. At the beginning of the conference, I was allowed to survey the forty-eight Congolese pastors present. Here I summarize some of the survey findings, using the results to raise questions for further consideration.

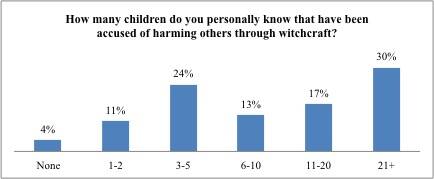

Personal knowledge of the accused (fig. 1)

I began by asking how many children these pastors personally knew that had been accused of harming others through witchcraft. While two of the pastors did not know any children that were accused of being witches, 60 percent knew at least six, and almost a third of the pastors said they knew 21 or more.

I was curious as to whether boys or girls were accused more often. At least in the experience of these pastors, while both are accused at high and relatively even rates, boys are accused at slightly higher rates than are girls.

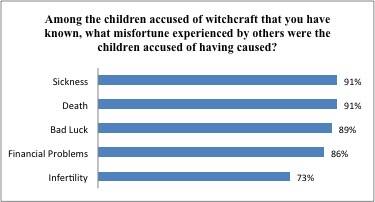

I wondered what these children were accused of having done to harm others, and probed a variety of areas.

Nature of harm accused of (fig. 2)

Fully 91 percent of the pastors knew one or more children accused of having made someone else sick, and the same percent (91%) knew one or more children said to have killed others. Nearly as many (89%) report children that were allegedly the cause of bad luck, with 86 percent reporting children that were blamed for having caused the financial problems of someone through witchcraft. Around three out of four pastors (73%) knew of situations where children were accused of having caused the infertility of adults through witchcraft. In short, these children were thought to be powerfully malevolent, able through witchcraft to harm, kill, and destroy.

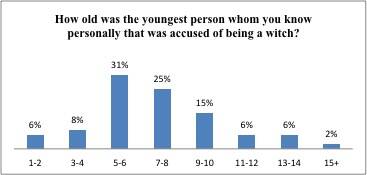

I wondered how old the children were that were being accused of exercising such incredible and dangerous power, and so asked, “How old was the youngest person you know personally that was accused of being a witch?” The following were the answers:

Age of the accused (fig. 3)

Most pastors (86%) knew children ten years old or younger that were said to have supernaturally caused the death and affliction of others, with 70 percent knowing children eight or younger, 45 percent knowing children six or younger, and three pastors reporting that they knew children one or two years old.

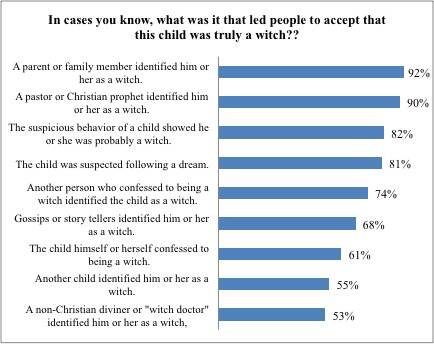

I wondered what the basis was for people to say this child was a witch. The following were some of the answers.

Fully 92 percent of pastors reported knowing cases where the accusation by family members of the accused led others to accept the accusation, with gossip (68%) sometimes also playing a role.

Reasons for the accusation (fig. 4)

Again 90 percent highlighted the role of pastors or Christian prophets in identifying the child as a witch. By contrast only 53 percent knew of cases where non-Christian diviners or “witch doctors” played a role in the accusations. That is, in modern Kinshasa it is under the authority of Christian spokespersons, not non-Christian, that such accusations are endorsed most frequently. Such Christian prophets and pastors, I was told, often make good money off of a ministry that claims the power to deal with child witchcraft.

Dreams either by the child or about the child are also sometimes treated as evidence that the child is a witch, according to the experience of 81 percent of pastors. Suspicious behavior on the part of a child (ranging from bed wetting, sleep walking, or having nightmares to simply being unhappy and socially withdrawn) were also often treated as evidence of witchcraft, according to 82 percent of pastors. Since these children have often had parents die, and in many cases have been sexually abused, the very symptoms of PTSD that they might naturally experience under such tragedies are themselves often taken as evidence that they are witches.

Finally the role of confession appears to be central. Seventy-four percent of pastors report that when some other person confessed to being a witch, they named a child as their witch accomplice, and this was taken as evidence against the child. And 61 percent of pastors report that the child’s own confession was key to their being treated as a witch.

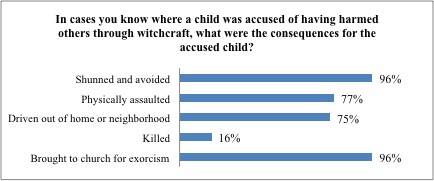

I wondered what were the consequences to the child of having people believe the child was a dangerous witch?

While relatively few pastors (16%) knew a child that was actually killed as a witch, everyone that knew such an accused child reported that they were shunned and avoided. And since the one thing orphan children need is others to love and care for them, to be shunned and avoided is consequential. Around 77 percent describe the child having been physically assaulted, and 75 percent say there were chased out of their home or community.

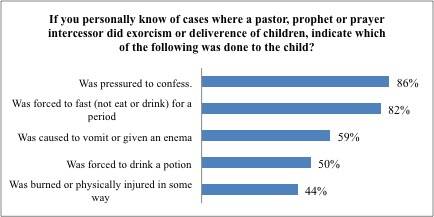

Every pastor that knew such children reported that some at least were taken to a church for the exorcism of a demon. To clarify what might be involved in such an exorcism ministry, I asked the following question:

Eighty-two percent of pastors say that in cases they knew of the child was forced to fast (to not eat or drink) for a period. Fifty-nine percent report that in situations they knew pastors (or others) tried to remove the witchcraft by causing the child to vomit, or with a purgative. Half said children had to drink a special potion. Nearly half (44%) say the child was burned or physically harmed in some way. And fully 86 percent say the child was being pressured to confess. That is, while food and drink is being withheld, while being forced to vomit, while sometimes being burned or cut or even sexually assaulted, the child is being pressured to confess.

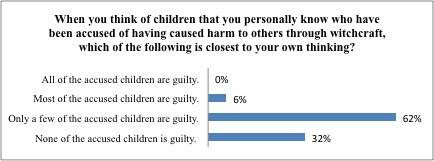

Perceptions of guilt (fig. 7)

I wondered what these pastors thought about the charge that these children had exercised dangerous power to harm others through witchcraft. And so I inquired about their perceptions of the guilt of the children. None of the pastors thought every child was guilty. Three pastors thought most of the children were guilty. Almost two-thirds of the pastors thought that only a few of the accused children were guilty. And almost one third did not think any of the accused children were guilty.

Of course many of the pastors at our conference were already working closely with these street children, and thus perhaps less likely than pastors in general to imagine that these children were incredibly powerful, evil, and dangerous beings (which the witch charge suggests).

Some Preliminary Questions

The results of this survey raise a variety of questions that we should be considering in the weeks and months ahead in the conversation at Sapientia:

- How should we assess the sorts of evidence people point to when they accuse someone of having harmed others through witchcraft—the evidence of such things as dreams, sleep walking, or confession?

- How should we assess the claim that the misfortunes (poverty, sickness, infertility, or death) of some people are to be ascribed to the powerful witchcraft agency of other human beings? Is there anything in Scripture to support such an idea?

- Why is it that people most frequently accuse unusually vulnerable people (such as old widows or orphan children) of exercising incredible witchcraft powers to harm others?

- If Satan is a deceiver, a liar, an accuser of the innocent, one who sows fear, discord, division, and death—then should we not consider the idea that Satan is operating through the accusers to mislead us about the locus and nature of demonic activity—and to encourage us to act towards vulnerable people the opposite of how God calls us to act?

- What should we think of the fact that today it is pastors and other Christian leaders, not non-Christian diviners or witchdoctors, who are at the forefront of accusing children of being dangerous witches?

The issues here are complicated and consequential—meriting the sustained attention we will give them in the weeks and months ahead.

Comments

Be the first one to make a comment!